NYU School of Law attracts notable practitioners, judges, and other professionals to teach upper-level administrative law and policy courses, in which they share personal insights and experiences, and encourage students to engage with actual case materials and to simulate practice.

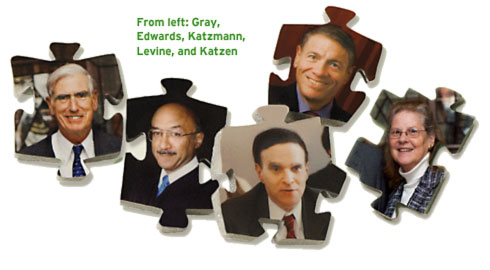

Senior Circuit Judge Harry Edwards of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit and his senior counsel at the court, Linda Elliott, teach Federal Courts and the Appellate Process and the Art of Appellate Decisionmaking. In those classes, students question when courts can review governmental action and when they are obliged to defer to government actors. To drive the lessons home, the students go into mock courtrooms, where, after they have been briefed on real cases that are before the D.C. Circuit, they present oral arguments to their classmates and teachers. Students then divide into panels of judges, deliberating and writing opinions. “It is very, very intense,” says Edwards, who has taught at NYU Law since 1989. “It is one thing to offer an intellectual critique of our system. It is quite another thing to have to comb through an actual case record to complete a brief, present an oral argument, or write an opinion.”

Robert Katzmann was teaching law at Georgetown University, specializing in such topics as regulation and administrative law, when President Bill Clinton appointed him to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit in 1999. Since 2001 he has also been teaching Administrative Process, a seminar in which he guides students in dissecting the various factors that affect an agency in reaching a decision, whether it’s the Federal Trade Commission or the Environmental Protection Agency.

“The administrative process is a many splendored thing,” says Katzmann, an adjunct professor, “and can be approached through many lenses.” He teaches students to look at the internal and external forces — the professional staffers and lawyers on the inside, for example, and the president, Congress, and the courts on the outside. Students roleplay as judges and critique opinions that Katzmann himself wrote, so he is able to replay the interaction between the courts and agencies.

C. Boyden Gray, former White House counsel to President George H.W. Bush, admits his bias when it comes to the importance of administrative law. He was trained as an administrative and antitrust lawyer from the beginning, and served as chair of the Administrative Law and Regulatory Practice section of the American Bar Association in the mid-1990s. He was also counsel to the Presidential Task Force on Regulatory Relief, chaired by then–Vice President Bush. “You cannot understand economic activity in the U.S. if you are a lawyer without understanding how congressional legislation is translated into the rules that apply to virtually every business entity in the country,” Gray asserts. Its importance, he adds, can be seen in the D.C. Circuit, which mostly hears administrative law cases. “It’s no accident,” Gray says, “that the principal feeder [of justices] to the Supreme Court is the D.C. Circuit.”

Gray taught at NYU Law for the first time in Spring 2010. His course, Energy, Environment, and Security: Law and Policy, pivoted on the idea that regulations primarily determine national and international energy policy. “It is a very tangled web of administrative rules and can only be understood in the context of very, very dense rulemaking,” he says. This spring, Sally Katzen, administrator of the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs under Clinton, will teach a seminar whose title echoes Gray’s statement: How Washington Really Works.

For five years, Distinguished Research Scholar and Senior Lecturer Michael Levine has taught a course called Regulation, Deregulation, and Reregulation that attempts to tie together regulatory theory with real-world problems. That intersection mirrors his career. As a student at Yale Law School, Levine wrote a note advocating airline deregulation, making him an early proponent of that concept. In the late 1970s, he was recruited to be chief of staff to Alfred Kahn, chairman of the Civil Aeronautics Board. From there he worked for airlines including Continental and Northwest, and became president and CEO of New York Air. He has also taught at Yale Law School. “Basically what I’m trying to do is give students the benefit of having seen the process from the government, business, and academic sides,” Levine says. Academics, he says, tend to “compare imperfect markets with perfect visions of how things could work.” People in the arena, he adds, tend to see markets as more or less as good as they are going to be. Levine tells students they’ll confront both imperfect regulation and markets, requiring them to figure out how best to navigate through them. Last fall, in light of the economic meltdown, Levine revised his course to address financial services regulation—a perfect example of imperfects.