Face Forward

Winston Wenyan Ma (M.C.J. ’98) has made every professional decision with an eye toward becoming the consummate global businessman of the 21st century.

Printer Friendly VersionOn January 28, 2012, the Economist did something it hadn’t done in 70 years: it launched a weekly section focused on a single country—in this case, China. The last country to receive such special treatment in the pages of the august publication was the United States, in 1942. The recent move was a belated acknowledgment of an increasingly apparent geopolitical and economic reality: if the story of the 20th century was of the rise of the U.S., the story of the 21st will be about the rise of China.

Those seeking to unravel the increasingly intertwined U.S.-China relationship generally look to Washington/New York and Beijing/Shanghai. That’s only appropriate, given the political and financial centers of the two countries. Those looking to identify crucial individual participants in that dynamic, however, should enlarge their North American focus a few hundred miles to the north, to Toronto, Canada. There, they will find Winston Wenyan Ma (M.C.J. ’98), the 39-year-old managing director and deputy chief of China Investment Corporation’s representative office in Toronto. It’s a mouthful of a title, but the gist of it is simple: Ma is China’s financial front man in North America.

Ask him to describe his job, and he will tell you that he is a simple investment professional tasked with a simple mandate: to seek out attractive investment opportunities for his employer, CIC, one of China’s sovereign wealth funds. That’s an honest description, but it deftly sidesteps the larger point: with some $482 billion in assets as of December 2011, CIC is currently the fifth largest sovereign wealth fund in the world, according to the Sovereign Wealth Fund Institute. And Ma’s specific focus is on investments in natural resources, among other sectors, that will help ensure that China can continue its remarkable economic transformation for years—and decades—to come. In 2009, for instance, CIC bought a $1.5 billion ownership stake in Canadian coal mining company Teck Resources and invested $1.58 billion in Virginia-based power company AES, in part to own 35 percent of its wind-generation business. Collectively, this makes Ma a key executive in the most fundamental financial transaction of our time: having lent the United States hundreds of billions of dollars during the debt binge of the last quarter-century, China is now converting that debt to ownership in some of the most crucial assets in the world. His job might be simple to describe, but it has profound implications.

U.S.-China relations are often viewed through a zero-sum lens: exchange rates are seen to benefit China at the expense of the American trade deficit, for example, and the use of overworked (and, by implication, underpaid) labor in Chinese factories makes iPhones and all manner of consumer goods affordable for the American masses. With Winston Ma, however, it’s not a case of one profiting at the expense of the other. His entire career is, in fact, an example of the possibilities of combination, especially the bringing together of people of diverse backgrounds for mutual benefit.

In the last three decades more than two million Chinese students have left home to study in another country. As keynote speaker at the Hauser Global Law School Program’s annual dinner in January, Ma played the historian and put himself in the larger context of waves of Chinese seeking broader opportunities.

The first wave was in the 1980s, when China opened up after the Cultural Revolution. This was a very focused group: the majority came to the U.S. for Ph.D.s in physics, chemistry, and engineering. “Most came on scholarships,” he said, “because they couldn’t have afforded to otherwise, and they were taking any chance they could to get out of China.” Many in that initial wave were happy to stay abroad after graduation, given the palpable increase in their standard of living. They bought homes, started families, and plotted a future in their adopted countries.

Ma arrived as part of the second wave. By the 1990s, China had been on a headlong course of economic development for 10 years and was reaping the initial benefits of modernization. Students began broadening their scope, taking law, management, and finance. “Many of us, myself included, were happy to join a big law firm or a bank, earn a great salary, and stay put,” he said. But he also noticed an increasing number of fellow expats returning to China.

The third wave of students began arriving after China’s entry into the World Trade Organization in 2001. That seminal event changed the face of the Chinese economy, creating a sizable number of Chinese millionaires: a 2011 survey by China Merchants Bank and Bain & Company reported that more than half a million Chinese have investable assets of more than $1.6 million, almost 60 percent of whom were considering emigrating. But more and more are returning home as well. “As China has become much more integrated in the global financial system and enjoyed huge economic growth, the focus is not on leaving China but returning to it,” said Ma. “Students now consider studying abroad to have opportunity costs as well as benefits.”

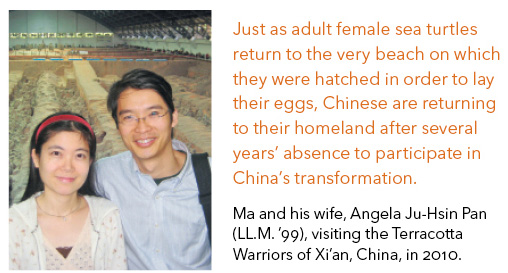

Even members of the first and second waves are today considering a return home after formative years abroad. The term bestowed on the increasing number of these Chinese is haigui, or “sea turtle.” Just as adult female sea turtles return to the very beach on which they were hatched in order to lay their eggs, Chinese are returning to their homeland in increasing numbers to participate in the remarkable transformation of their country. Ma became a sea turtle himself in 2008. Before he did, though, he spent a decade deliberately becoming a bilingual, bicultural businessperson. A coveted one. “There’s an endless appetite on both sides of the water for people with the expertise that Winston has. People who are not only very knowledgeable about the business world, but who know how to commute between two very different political-legal cultures with very different values, attitudes, and experiences,” says Professor Jerome Cohen, co-director of NYU’s U.S.-Asia Law Institute, who was, in the early 1980s, the first Western lawyer to practice in Beijing. “We just don’t have anything like the number of people we need, on both sides.”

As exchanges around the globe eye Greece with concern, there is no doubt that our world is shrinking and enmeshed. We should all care how China fares in investing its trillions, says Cohen. Consider Japan in the 1980s and ’90s, he adds. “Japan did not invest wisely in the U.S. Its subsequent economic difficulties created tensions between the countries that might have better been avoided.”

Ma was born in July 1973 in Suzhou, the historic silk capital of China, which boasts numerous lakes and interconnecting canals and about 150 classical Chinese landscaped gardens. Known as the Venice of the East, it is only about 40 minutes by commuter rail from Shanghai. Ma enjoyed a middle-class youth there as the second child of two high school teachers. (His sister, Xiaoyan, lives with their mother and works for the Suzhou government.) After a strong showing in high school, he entered Dalian Military Academy in Liaoning Province for a compulsory one-year course in military training as a member of Fudan University’s Class of 1990. Along with Tsinghua and Peking Universities, Fudan, established in 1905 in Shanghai, is considered one of China’s most elite educational institutions.

Ma earned a bachelor of science degree in electronic materials and silicon devices in 1995, graduating first in a class of 23. While a number of Ma’s classmates then took the obvious route, snagging jobs at places like Intel and Singapore Semiconductor, Ma had other ideas. With an eye already on U.S.-China relations, he decided that he would dive headlong into the middle of a raging debate of the time: software piracy. The two governments were in the midst of negotiating a pact to help protect American software, and Ma saw an opportunity to be a pioneer in intellectual property protection in China. “It was a chance to combine knowledge of American culture, technology, and crossborder issues,” he says. So he decided to go to law school to round out his expertise. He didn’t go far, enrolling in a post-undergraduate degree program at Fudan’s own School of Law.

Ma graduated at the top of his class once again—this time the first of 32. But he soon realized he’d made a miscalculation. Intending to stay ahead of the curve, Ma actually might have been too far ahead of it when it came to intellectual property in China. The epiphany came, he says, when he visited a friend in the graduate dormitory at Fudan and watched a steady stream of students come knocking at the door to buy versions of pirated software that the friend kept stashed under his bed. “At that moment, I knew it was the wrong choice of career,” he says. “I was way too early. It was the right path, but it wasn’t really taken seriously until after the turn of the century.”

It was time to change directions, and as luck would have it, NYU Law sent a contingent of professors to lecture at Fudan during Ma’s final year of law school. Led by John Pagan, then head of the school’s Hauser Program, the effort was a trailblazing one. The program, conceived in 1995, set out to invite about a dozen international scholars each year to join the NYU Law community. But it came with a remarkable twist: the program would fully fund the candidates. Law schools rarely gave scholarships to foreign students at the time, and to find one that included a full ride—airfare, board, and living expenses—was almost unheard of. Hauser was charting a new course, though, and had Ma in its sights from the very beginning.

The only problem? It had its eyes on another student as well, Chinese student that year, Ma seemed destined to do something very uncharacteristic: come in second place. While his parents had provided for top schools, financing a foreign education was another thing entirely, and when he learned from Pagan that he wasn’t the frontrunner, Ma says he faced the depressing prospect that he might not get a U.S. law degree. (Harvard Law was ready to have him, but he’d have to finance it himself.)

Then he got “the e-mail.” Pagan informed him that his rival for the scholarship had chosen to go to Harvard. Hauser wanted Winston Ma. Pagan, who currently teaches law at the University of Richmond, jokes that Ma’s memory must be failing him. “I can’t believe that we ever considered him our number two choice,” he says. “I recall him as a brilliant, focused, and highly motivated young scholar.” Ma impressed Pagan to such a degree that Pagan later invited him to teach at Richmond as a visiting international scholar. “I’ve never met the guy who chose to go to Harvard,” Ma says now. “Maybe I should track him down and thank him.”

When Ma flew from Shanghai to New York, it was his first trip out of China. He joined a mini-U.N. of young scholars—his Hauser cohorts hailed from Australia, China, Germany, India, Israel, New Zealand, the Philippines, and Venezuela—and he even met his future wife, Angela Ju-Hsin Pan (who enrolled from Taiwan one year after Ma, earning an LL.M. in 1999), at the school. Even if publications like the Wall Street Journal still hadn’t grasped the paradigm shift in China’s global economic position—Ma remembers having to read well into the newspaper to find any stories about China—he knew he was part of a select group of native Chinese speakers who would soon be in a position to help shape history.

While Ma narrowed his focus to capital markets law during his studies at NYU, he says the coursework that initially resonated with him was about civil procedure. In a course taught by Andreas Lowenfeld, Herbert and Rose Rubin Professor of International Law, he was flabbergasted by one of the very first issues, that of constitutional law and the matter of jurisdiction. “I’d had a legal education, but I’d never heard of civil procedure being discussed in the context of constitutional law,” Ma recalls. “It was also the first time I got to see the eloquence of a Supreme Court justice opinion.”

The lawsuit in question was a famous one: International Shoe v. Washington, a landmark case in which the Court established a number of legal rules, from corporate participation in interstate commerce in state unemployment compensation funds to the due process clause of the 14th Amendment. “They were talking about whether it was fair to have a case like this, before even addressing the substantive question of whether they were for or against,” says Ma. “The opinion by Chief Justice Harlan Stone was one of the most eloquent I have ever read. I still remember some of the exact words, like the fact that a lawsuit cannot ‘offend traditional notions of fair play and substantial justice.’ I was also amazed that a professor would be so familiar with a case written by a judge. In China, you opened up a book and looked up the penalty for the charge. Here, it was much more of an engaged discussion.

“I went to Chinese law school from an engineering background,” he continues, “where everything is structured. Chinese law was like that too, with the Supreme Court issuing opinions not in essay format but merely saying, ‘These are the standards, and this is how we’re going to apply them in court.’ Contractual law, for example, might say that if there’s a dispute about a contract, then the jurisdiction should be at the defendant’s side, because if you want to bring a case, you bring it at their jurisdiction. It’s a very practical approach to the law. In China, I would never have paid that much attention to legal theory, as practical rules ultimately prevail. So what really fascinates me about the U.S. is that it’s actually much more sensitive to the facts. There are general themes, but the facts are all different and unique, and thus require a better appreciation of cultural history. My civil procedure course at NYU was the starting point for me of a more balanced understanding of language and culture and social concerns.”

In particular, says Ma, his NYU Law studies showed him the value of understanding the human factor in business and social dealings, and of being aware of precedent and history. “In this interconnected world, understanding other people’s cultural traditions, historical backgrounds, and social values is critical,” says Ma. “When you’re working in the derivatives business, you’re dealing with the most complicated financial models that are out there. But I also spend a lot of time trying to understand the people on my side and the counterparty side.” Even today, in a continuing attempt to understand Anglo-Saxon culture in an English-dominated world, he goes the extra mile. Beside his bed is a volume of Shakespeare.

Armed with a degree in international economic law, Ma dived right into corporate and capital markets work in a succession of jobs with increasing responsibility at Davis Polk & Wardwell, J.P. Morgan, and Barclays Capital. He detoured exactly once, by leaving Davis Polk for the University of Michigan in 2001 to pursue an M.B.A. and a master’s in engineering with an eye to hitching onto the tech boom bandwagon. When the tech bubble burst partway through his M.B.A., he finished his degrees but headed to Wall Street.

Ma’s focus was capital markets, specifically, sophisticated equity derivatives. At Davis Polk, Ma’s initial strategy had been to take on as much local U.S. work as he could, with the goal of being seen on par with his American associates and not just as someone with a specialty in speaking to Chinese clients or to Chinese on behalf of U.S. clients. So while he did work on initial public offerings for Chinese companies, he made sure it was only part of his workload. He took the same approach at his Wall Street jobs. While he helped Chinese companies looking to learn about (and use) novel financial products developed in the U.S. market, he also made sure to play a significant part in U.S.-centric transactions.

One notable example: in July 2003, J.P. Morgan partnered with Microsoft to create a one-time transferable stock option program that allowed holders of underwater Microsoft options to sell their options to the bank. Some 51 percent of Microsoft employees, representing 55 percent of the eligible shares, chose to do so in one of the largest equity derivative transactions ever—$8.8 billion worth. In this and other instances of J.P. Morgan’s entering into derivatives trades on its own balance sheet, Ma frequently served as one of the firm’s main financial engineers.

Linda Simpson, the partner overseeing Davis Polk’s equity derivatives capital markets business, says Ma uses all the available tools at his disposal to get his job done neatly and cleanly. “Winston is nothing short of a Renaissance man,” she says. “On one deal, he realized that all the other lawyers had overlooked an interesting mathematical issue about the pricing of one security. He wrote letters to professors about the issue, and they wrote him back. I was blown away. How many associates do that?”

Simpson also noticed something that most people who work with Ma have seen: regardless of what job he happened to be doing at any point in time, he didn’t just get buried in the details; he also stepped back to take a wide-angle view. When working with Securities and Exchange Commission regulations on a specific derivatives deal, he would also ask: How should the Chinese securities officials regulate local markets in China? How will China adopt usage of new kinds of derivatives that the U.S. is introducing? “He is a terrific U.S. lawyer,” says Simpson. “But he is also a lawyer with a Chinese law degree and an M.B.A. There aren’t that many people with qualifications like that, and it’s no surprise that he’s now become extraordinarily valuable to China as well.”

Beyond his day-to-day role in structuring financial products for clients at J.P. Morgan, Ma was often brought in as a translator of China-specific issues that his New York colleagues found more difficult to understand than the usual concerns of U.S.-based issuers. When Chinese companies sought U.S. financing, for example, the country’s foreign exchange system required establishing offshore financial affiliates that served as pass-through vehicles for transactions that couldn’t be done directly in China itself. “It was pretty confusing to some of my New York colleagues,” says Ma. “And I played a particular communications role in bringing them up to speed on how the transactions worked.”

Ma has a knack for making complex products understandable, despite English being his second language. In every trading desk he has worked on, Ma has been known as a patient teacher of younger and less experienced traders, and he has even helped CFOs and treasurers of client companies polish their own communications with such constituents as investors, rating agencies, and regulators.

Starting from his first job at Davis Polk, Ma began honing his writing skills in English, contributing numerous articles on legal and other technical matters regarding derivatives to the newsletter Derivatives Week’s “Learning Curve” column. He eventually published some 20 articles on derivatives pricing, trading theory versus practice, and capital markets innovations in China.

Eventually, Ma’s ambitions grew and he began working on a book that capitalized on his position as a Chinese national on Wall Street. His 2006 opus, Investing in China: New Opportunities in a Transforming Stock Market, is one part investing textbook and one part treatise on the ongoing developmental challenges still facing Chinese securities markets. The publication turned Ma from a well-regarded banker and lawyer into an internationally quoted expert on China’s markets and legal system. Rather than being merely Chinese Investing 101, Ma’s book characteristically demystified all manner of complex topics, including multiple derivative securities; the differences, due to local regulatory and legal frameworks, between Chinese and Western investment products; and the overriding influence of China’s particular brand of state-owned capitalism on its securities markets.

“It wasn’t just cheerleading,” says Richard Sylla, Henry Kaufman Professor of the History of Financial Institutions and Markets at NYU’s Stern School of Business, who wrote the foreword. “He also provided some warnings, in particular about those enterprises that were majority-owned by the state. He pointed out that if China followed the path of other countries, they would privatize these things. He didn’t make an explicit argument, but by talking about it, he was tacitly endorsing the idea. And that’s just what they did, with the result that China became much more attractive to foreign investors.”

Ma sees the book as a major turning point in his career. “After my book, it had become very clear that I might prove a valuable link between China and the U.S.,” he told a reporter. Indeed, senior Chinese bureaucrats were now noticing their countryman as well. Peter Zhang, deputy director general of the China Banking Regulatory Commission, offered high praise in a book blurb: “His expertise in both legal and financial areas combined with his understanding of the Chinese financial system make the book attractive to those interested in the Chinese financial markets, particularly in the legal aspects and market innovation.”

In late 2006, Chinese authorities established the country’s first derivatives trading exchange, the China Financial Futures Exchange. The first product was an index futures contract. Soon thereafter, the Shenzhen Stock Exchange organized an annual China International Derivatives Forum, where Ma was an “international expert” speaker and usually the sole Wall Street representative from the North American markets. Even at that late date, few Chinese had made it to the front office of a U.S. trading floor.

Remarkably, the increased attention didn’t go to his head. When it was suggested that he translate his book into Chinese, he demurred. “I’m of the view that local people always know the situation the best, and it seemed to me that Chinese people didn’t need advice from someone sitting in New York on how to invest in their own markets,” he says. “I think about the guys who were paid to watch bicycles outside the Shanghai Stock Exchange in the 1990s, at 10 cents per bike. They could probably read the market up and down much more sensitively than I could have, just by counting the number of bicycles out there.”

At Barclays, where he had ascended to the title of deputy chief of the convertible and equity solutions group, Ma began a series of dinners modeled on the salons of the 19th century, inviting bankers, lawyers, journalists, regulators, and businessmen interested in the broad topic of China for evenings of inspired conversation.

The effort was another example of Ma’s deliberateness. “He called them ‘China dinners’ and invited a select group of people he thought would mesh well,” says Ruth Sherman, a communications consultant who attended a few and who had worked with Ma on improving the cultural aspects of his speech. “Winston guided the conversation at those dinners; he showed that he knew the value of being a connector—something that is obviously highly valued in the business world. He understood that intuitively.”

One topic that consumed the group at more than one dinner: the “Made in China” miracle after the country’s entry into the World Trade Organization in 2001. Ma’s guests debated the big questions: Why had China become the world’s manufacturing center? How long would its competitive advantage last?

Ma’s co-host, Michael Zakkour, who at the time was running a consulting firm for U.S. multinationals, says dozens of friendships came out of the dinners, as well as business partnerships. “We put together some of the best intellects in New York and beyond for those salons,” says Zakkour, who marvels at Ma’s cross-cultural fluidity. “He comes across as both Chinese and American. Winston is one of those rare characters who can live, work, operate, think, and act in both cultures.” Zakkour lived in Beijing for four years and continues to commute to China regularly. He points out that there are lots of people who can learn Mandarin and then speak to Chinese natives by substituting Chinese words in American phrases and syntax. But the brilliant ones, he argues, speak in a cultural and social context as one Chinese would to another. “That’s a whole degree of difficulty higher,” says Zakkour. “And Winston has done it, only in reverse.” Frank Guarini ’50 (LL.M. ’55), the 88-year-old seven-term New Jersey congressman who counts Ma among his friends, agrees: “He is a man of the future—someone who will be a major player in the business world of tomorrow.”

Among friends and coworkers, Ma is always quick with a joke or, somewhat surprisingly, a line straight out of a Hollywood blockbuster. Salim Mawani, who worked with Ma at Barclays Capital, recalls a never-ending string of movie one-liners that poured out of Ma deep into long nights on the trading desk. Ma’s memos to colleagues often began with references such as “Houston, we have a problem,” from Apollo 13, or “We will not vanish without a fight!” from Independence Day.

Ma readily admits to being a movie buff, but points out that it was also a subtle way for him to practice English with his colleagues instead of getting mired in legalese or banking-speak. As usual, his cultural barometer is unerring, to the point where he has a genuine appreciation of good, old-fashioned raunchy American comedy. “I like Old School,” he says, referring to the 2003 frat boy favorite starring Will Ferrell, Vince Vaughn, and Luke Wilson. It is hard to imagine, but the fact is that behind the otherwise formal and polite demeanor, Ma laughs along with his trading floor peers at R-rated comedies. When asked of other ways Ma finds to blow off some steam, his wife, Angela, says he enjoys relaxing and having a beer while watching the New York Knicks. He is also an avid runner and swimmer, and a self-taught student of Chinese medicine. Plus, he enjoys cooking; one of his specialties is eel.

Ma is also a perfectionist, which his wife acknowledges can be irksome to a self-described “normal” person such as herself. “He has ‘correct’ attitudes toward almost everything,” she says. “He eats healthy—fruits and vegetables—likes to exercise, and likes to go to bed and get up early. Winston values efficiency and is always working on something productive. That’s basically a good thing, but it can occasionally be annoying.”

Describing Ma as a perfectionist seems suspiciously like the answer to the cliché interview question, “What is your greatest weakness?” Only in this case, it seems to have the virtue of truth. Winston Ma is a perfectionist, in both his personal and professional life: always on message, always proper. It can make it a little difficult to get a read on him as an actual person, but spend enough time with him and you will see a twinkle in his eye.

Not that Angela Ma doesn’t have her own drive. Since earning her LL.M. from NYU Law, she has passed the bar in three jurisdictions—Taiwan, the United States (New York), and China—and has worked for law firms and banks herself. In the past dozen years, though, she has moved four times in support of her husband’s career. Now she is writing her dissertation on ownership issues regarding stolen art and looted cultural property to earn a J.S.D. at the Central University for Nationalities, in Beijing.

In 2007, Ma recalls, he and another colleague from Barclays, Dev Shrotri, would have numerous conversations asking each other why they were watching from afar as their respective countries were undergoing massive economic transformation. “We were a Chinese guy and an Indian guy working for a British bank,” says Ma. They named it their “Chindia” quandary. And then they acted: Dev went to India to work on a start-up, and Ma went to Beijing.

As much as recent headlines about China’s government emphasize that connections and nepotism are still a common way to land lucrative jobs, Ma found his position in a surprisingly old-fashioned way: by answering a help-wanted ad.

China Investment Corporation was founded in 2007 as a wholly owned entity of the Chinese government. According to its 2011 annual report, it is “a vehicle to diversify China’s foreign exchange holdings.” Like the Chinese government itself, the fund takes the long view, and has elucidated plans to evaluate performance over a 10-year horizon. CIC posted recruiting notices in the Financial Times and the Wall Street Journal, and Ma submitted his résumé without having any personal contacts there. (He’d met the fund’s president, Gao Xiqing, at a speech at NYU but had not run into him again until his interview.) Ma got the job, joining the fund in May 2008 as a managing director in the special investments department in Beijing. He took a pay cut and became a “sea turtle,” but says the pride of working for his country and the fact that he is once again on the cutting edge of global finance more than make up for it.

His transformation has not gone unnoticed. “Winston Ma is at ease in both Eastern and Western cultures,” says Gustave Hauser (LL.M. ’57), a cable television pioneer who with his wife, Rita, a member of the President’s Intelligence Advisory Board, founded NYU School of Law’s eponymous program. “He understands the nuances between the two cultures. Not only that, he is intellectually stimulating, socially adept, and gregarious. People like him. And the Chinese government has clearly recognized his competence by giving him such great responsibility.”

Since joining CIC, Ma has had leadership roles in major direct transactions in mining, energy, agriculture, and financial services sectors. He mentions that he is working with the Canadian heads of Chinese companies to establish the first-ever China Chamber of Commerce in Canada, which will include finance and information technology companies in Toronto, energy companies in Alberta, and mining companies in British Columbia and Quebec. But he is otherwise understandably reticent about discussing his specific duties, given the political sensitivity of his post. Nonetheless, all signs point to Ma’s enjoying the favor of his superiors. “Winston’s education and training in law have enabled him to be more effective in his work at our company,” says CIC president Gao. “In particular, the analytical capabilities and sensitivity to risks required of a lawyer prove to be valuable to a large financial investor like CIC.”

What are Ma’s views on China’s particular version of state capitalism? Or the Chinese aphorism “The state advances while the private sector retreats”? If Ma has opinions, he’s not sharing them. “I’m just acting as an investment professional,” he repeats, perhaps the only time over the course of several discussions with Ma that his answer seems programmed and not considered. CIC’s mandate makes clear it is a financial investor and does not seek corporate control. Returns have been solid, if not extraordinary. Despite a 4.3 percent loss in 2011, the fund has registered a 3.8 percent annual return since 2007.

Steer Ma away from the confidential details of his day-to-day job, and it’s possible to engage him in an area he enjoys speaking about: what we can learn from history and how we can use its lessons to better ourselves and our relationships today. He likens the current mutable state of global capital markets to the shifts that faced the Solvay Council in 1911, when physicists were confronting earthshaking discoveries in the quantum realm that threatened the foundations of a discipline rooted in the notions of Isaac Newton and James Clerk Maxwell. Solvay was convened as a cooperative focused on intellectual debate and collaborative efforts. Ma sees both the Hauser Program and his job at CIC as similar opportunities to move the dialogue forward about a still rapidly changing world.

And indeed, Ma is one of an extremely select group of people with the experience, education, and background to provide a bridge for constructive dialogue between China and the United States as they feel out their respective positions in a new world order. “Each government must work to build domestic security and prosperity to fit its own unique political, economic, geographic, cultural, and historical circumstances,” Ma said in his Hauser dinner keynote in January. “But there must be cross-border conversations and brainstorming in the broadest possible context, and NYU and the Hauser Program are the perfect venues for that. This historic time of the century calls for the collective effort of the NYU community—each and every one of us.”

—Duff McDonald is a contributing editor at Fortune. He is at work on The Firm, a history of McKinsey & Co., due from Simon & Schuster in 2013.

—

Ma is named one of 21 Young Leaders in 2013 by the Asia Society

Ma profiled in Dividend, the magazine of the Univeristy of Michigan Ross School of Business