Bringing the Law to Life

NYU’s Clinical Program Helps Students Change the World—One case at a Time

Printer Friendly VersionShackled by the wrist and ankle to two other boys, Paul could only watch as floodwaters caused by Hurricane Katrina began rising in his New Orleans prison cell, entering from the drains, toilets and sinks, eventually reaching chest level. Only 15 years old, Paul had been detained for violating probation for marijuana possession, but was transferred along with other kids from juvenile detention to the adult population of Orleans Parish Prison when the sheriff made the ill-fated decision not to evacuate his charges. Most of the prison staff fled, and the adult prisoners threatened to riot, while Paul went without food or drink; some of the other children ate the hotdogs and pieces of cheese that floated by them in the filthy water. The prison was evacuated two days later, and after a frightening week under armed guard outdoors alongside angry adult criminals, Paul was placed into state custody and sent to a detention center in Shreveport. He had no idea what had become of his family, who had lived in the devastated lower Ninth Ward—and no one could tell him. He was afraid his parents had drowned.

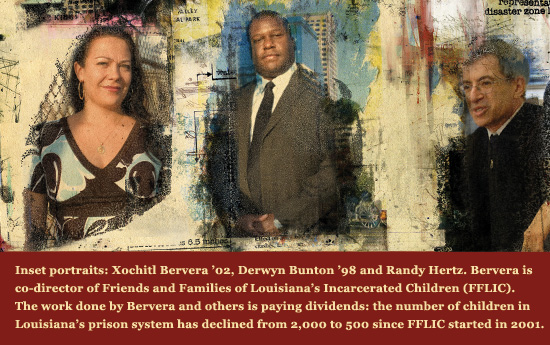

“Standing there talking with that kid, it struck me so deeply that we were it for him,” says Derwyn Bunton ’98, associate director of the New Orleans-based Juvenile Justice Project of Louisiana, who met Paul a month after his harrowing ordeal. “This child was 500 miles from home, wondering if his family members were alive or dead. If we didn’t step in to help him, no one would.” The Juvenile Justice Project (JJP) got to work. Bunton worked with the Louisiana Office of Youth Development to find the boy’s parents, who had fled to Dallas, and went to New Orleans Parish Juvenile Court to obtain a release order that closed Paul’s case. He arranged for a youth advocate to travel with Paul to Dallas where Paul finally rejoined his family. And in May 2006, the JJP published a scathing report coauthored by Bunton: Treated like Trash: Juvenile Detention in New Orleans Before, During and After Hurricane Katrina. The report, which found that the storm had merely exacerbated and made blatant the huge problems of a juvenile-justice system that was dysfunctional long before the storm hit, garnered international media attention from publications such as the United Kingdom’s Guardian, the Los Angeles Times and the New York Times.

For Bunton, tracking down family members and arranging transportation is as much a part of his job as writing policy reports. He credits the Juvenile Defender Clinic taught by Professors Randy Hertz and Kim Taylor-Thompson and former Adjunct Professor Jacqueline Deane ’85 for teaching him how to help clients who are often as much in need of food and shelter as legal representation. “Everything we did in the NYU clinics, we do here,” says Bunton. “We work for the clients any way we can—through litigation, policy work, outreach, mobilization and organizing. The clinic taught me to think about clients and find ways to address their needs through legal and policy changes. Those lessons continue to pay dividends today.”

As Bunton’s story demonstrates, even one person can make a huge impact on the life of an individual and a community. For nearly 40 years, NYU School of Law’s Clinical and Advocacy Programs have been offering committed, bright and talented students an unparalleled introduction to the challenges and rewards of hands-on legal practice. In turn, these lawyers have fought poverty, injustice and political repression in New York City, across the nation and around the world. “I am struck by the passion and commitment of NYU’s clinical faculty, the commitment of graduates to pursue careers in the public interest, and the wide range of scholarship that influences understanding of clinical education for students, lawyers, judges and scholars,” says Charles Ogletree, the former vice dean of the Harvard Law School Clinical Program who is the Jesse Climenko Professor of Law at Harvard and director of the Charles Hamilton Houston Institute for Race and Justice.

More than just a means through which students learn to practice, however, the clinical program influences the character of the Law School. “NYU has a vibrant commitment to public-interest law and advocacy,” says Kevin Ryan (LL.M. ’00), the first-ever commissioner of the New Jersey Department of Children and Families. “Public-interest advocacy is intentionally nurtured as part of the law school experience. The faculty create real oxygen for students to discover how law can become a tool for social change.”

A Revolution in Legal Education

Clinical education at the NYU School of Law began in the late 1960s, as an outgrowth of those turbulent times. “The call in education was for ‘relevancy,’ and that call affected law schools perhaps more than any other educational institution,” says Martin Guggenheim ’71, Fiorello LaGuardia Professor of Clinical Law. Students agitated for legal education that was better connected to the real world.

Such an education would make a significant change from the status quo of that day. “Law schools had been around for a century, and had mostly shunned anything to do with practice,” notes Harry Subin, professor of law emeritus. “They didn’t hire people with experience in practice, and they were more concerned with scholarship than with training lawyers.”

These 1960s students wanted experiential learning that was framed against the concerns of the day: Vietnam, civil rights, and the 1963 U.S. Supreme Court case Gideon v. Wainwright, which institutionalized every defendant’s right to counsel. “Students really believed they knew better than their teachers what they should be learning and what the curriculum should include,” says Guggenheim. “We demanded—that’s how we spoke then—that our education give us opportunities to provide service to underrepresented groups and to learn to be practicing lawyers.”

The students championed the writings of Jerome Frank, the late federal judge and former Yale professor, who had published a series of articles back in the 1930s maintaining that law schools taught nothing but theory because no one on the faculty knew what it was like to actually practice law. “Sometimes ideas need to be articulated when the time is right. His ideas fit perfectly with the times,” recalls Guggenheim.

Meanwhile, Gideon had also created a need for lawyers who knew how to handle themselves in a courtroom. Justice William Brennan Jr. and others argued that one good way to provide lawyers for defendants was through clinical legal education. In response, the Ford Foundation, through its grantee, the Council on Legal Education for Professional Responsibility (CLEPR), offered generous grants to law schools that were willing to provide clinical legal education. “The confluence of factors—the students’ demand for relevance, the legal establishment’s support for clinical education, and the resources made available by the Ford Foundation— gave clinical education its foothold,” says Guggenheim.

Beginnings at NYU

The availability of funds played a major role in convincing the Law School faculty and administration to initiate clinics at NYU. “Most faculty treated the offer as a freebie,” says Guggenheim. “They weren’t against the idea philosophically, and since it didn’t come at the expense of other courses, they thought, ‘Why not?’”

The Law School recruited Subin, a Yale Law School graduate, to teach its first clinic, Criminal Law, in 1969. Subin had held positions with the Department of Justice and the Vera Institute of Justice, which works with governments and organizations throughout the world to improve criminal justice and public safety programs. Subin had no special interest in clinical education, but the Ford Foundation funding covered an eight-month clinical teaching position at NYU and the job sounded interesting.

It was. The eight students in the first Criminal Law Clinic represented indigent defendants in the New York City Criminal Court, and called themselves the CLEPR 8, to honor the grant that funded the clinic. The label suited the times. “It was in vogue to be a member of some underground movement,” says Subin. “They really wanted to fight the good fight.” He was struck by the passions of the clinical students, especially compared to his own 1950s peers. “Law students in my day were 50 years old before they were 25. These NYU students were a different story. They were politically involved. They weren’t rioting on the fringes, but interested in the causes: feminism, race problems and treatment of the poor.”

Subin became the first chair of the Clinical Programs Committee at NYU and was centrally involved in the expansion of the clinical curriculum in the 1970s and early ’80s. Faculty who joined the clinical program during this time included Claudia Angelos, who had been a lawyer for Prisoners’ Legal Services of New York; Paula Galowitz and Lynn Martell, both civil attorneys for the New York Legal Aid Society; Guggenheim; Chester Mirsky, who was a senior trial attorney at the Criminal Defense Division of MFY Legal Services, and Laura Sager, who enrolled in law school after participating in the Selma civil rights marches of 1963 and 1964.

Meanwhile, across the country Anthony Amsterdam was serving as Montgomery Professor of Clinical Legal Education at Stanford University School of Law. Amsterdam had earned the first endowed clinical chair in American legal education in part by amassing a nearly unparalleled record of civil rights and capital defender victories, including Furman v. Georgia, the 1972 Supreme Court case that resulted in a divided court ruling the death penalty unconstitutional. (See “A Man Against the Machine” on page 10.)

By 1981, Amsterdam had been teaching at Stanford for 12 years and longed to move back East—he is from Philadelphia—and settle in a big city. NYU’s clinics—which were among the top three programs in the nation and had the faculty support to aim even higher—piqued his interest. “I thought NYU was in a position to help create a new era in clinical education,” says Amsterdam, who took over the program that year and ran it until 1988.

Amsterdam’s arrival brought high-octane star power to the clinical education program. “When Tony joined the NYU faculty as the first faculty director of Clinical and Advocacy Programs, he was considered among the elite in three separate spheres: legal scholarship, education and practice,” recalls Guggenheim. “His rare status as a triple threat made him uniquely qualified to reshape and reconceptualize clinical education at NYU.” Perhaps more important, Amsterdam brought innovation, scholarship and a passion for clinical teaching that didn’t exist among law schools at the time—and is still rare today, even at top institutions.

From Clinics to a Clinical Program

Amsterdam held the opinion that 20th-century legal education was too narrow. Most law schools focused exclusively on teaching students to think analytically within a specific body of law—mainly the traditional first-year areas of contracts, torts, property, civil procedure and criminal law. “I thought legal education should include an examination of lawyer’s thinking, planning, decision-making and performance in practice,” he says. “I believed that examination should engage the same exacting critical analysis that law schools had traditionally applied to substantive legal doctrine.”

To that end, he designed the first integrated clinical curriculum, which reorganized the clinics into a three-year series of related learning experiences. The new curriculum included a seminal first-year lawyering course taught in seminar-sized classes that was devised by Amsterdam (originally as an experimental course at Stanford) using simulations, or role-playing, to develop critical ways of thinking about a lawyer’s basic practice skills such as interviewing, negotiation, witness preparation and drafting. “Teaching the course was like sky-diving off the edge of the known law school universe, and hoping that a conceptual parachute would open before we hit bottom,” says Amsterdam.

[SIDEBAR: Where it All Begins]

Open it did. Lawyering, which became a mandatory full-year course in 1986, has grown into its own program with a 16-member lawyering faculty led since 1999 by Peggy Cooper Davis, the John S. R. Shad Professor of Lawyering and Ethics and a former Family Court judge. (See “Where It All Begins,” below.) In March, the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching released a two-year study that held up Lawyering at NYU as a model for “induct[ing] students into an understanding of how this complex system of society’s self-regulation works—or should work—to uphold and extend socially vital ends and values, and to put students on the path toward developing expertise as practitioners of the legal art.”

Amsterdam’s curriculum continued in the second year with more simulations, typically following a case or fact pattern for the entire semester. Cases such as the trial of a teenager accused of robbing a convenience store, with a victim who didn’t get a good look at the alleged perpetrator and a witness with credibility problems, would allow the instructor to control the progress of a case to create learning opportunities. Students can shift roles in order to develop multiple perspectives on a single situation. For example, acting as a witness motivated to lie or a prosecutor who asks a question and gets an answer that damages his or her case. Students can review themselves and critique their classmates’ performance by watching footage of their role-playing. They can also review a trial in its entirety, an experience that gives them an opportunity to reflect on alternative approaches to various circumstances. State-of-the-art simulation rooms in Furman Hall are equipped with microphones suspended from the ceiling and separate video rooms where the action is filmed from behind a glass wall.

Finally, third-year students could elect to take fieldwork clinics where they represent actual clients. Over the years, fieldwork clinics have become an option for second-year students as well. “Tony’s approach was groundbreaking because it created a sequenced set of lessons that all built on the foundation of lawyering,” says Randy Hertz, the current director of Clinical and Advocacy Programs. “That sequence still sets the program apart: an overarching conceptual structure that defines what students can learn through clinical teaching and then finds the best way to provide that learning experience over a three-year cycle.”

The clinical program’s new structure drew more students into the program, and Amsterdam recruited professors, including Hertz, who came from the Public Defender Service of the District of Columbia; Holly Maguigan, a former criminal defense attorney from Philadelphia, and Nancy Morawetz ’81, who came from the Civil Appeals Unit of the Legal Aid Society of New York. The faculty also drew closer together under Amsterdam, meeting together regularly to talk about their goals for students.

In reflecting on the clinical program’s growth during the 1980s, Hertz, Guggenheim and others fondly remember the positive and creative contributions of Chester Mirsky, who passed away in 2006. Mirsky developed the Federal Defender Clinic, which evolved from the Criminal Law Clinic he cotaught with Harry Subin, and innovated another course with Subin called Criminal Procedure and Practice, which taught doctrine such as the law of bail and search and seizure, and used simulations to teach skills such as motions to suppress and how to do direct and cross examinations and make closing arguments. “The students loved it,” Subin says. “In terms of really understanding doctrinal law, it just brought it to life.”

In 1985, the clinical program achieved another milestone when Guggenheim became NYU’s first full professor of clinical law, beginning a tenure track for clinical professors that was in the vanguard for American law schools.

Recruiting a Diverse Faculty

In 1971, NYU became the home of the Juvenile Justice Standards Project, which lasted 10 years and produced 23 volumes developed by national juvenile-justice experts across a range of disciplines. The chairman of the project, the late Chief Judge Irving R. Kaufman of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, suggested that NYU create a juvenile-justice clinic. Robert McKay, then dean of the Law School, went looking for someone to direct the clinic.

Martin Guggenheim got the job in 1973. He thought he’d stay for a year or two, but he found that he loved teaching in a clinical setting. It wasn’t long before Guggenheim realized he was learning a great deal about his profession through the craft of teaching it to his students. “I now was obliged to reflect analytically on the things I did as a lawyer,” he recalls. “I realized that there was a blueprint, which I was learning myself by teaching it to my students. I became a much better lawyer by teaching them to be lawyers— and the same thing is true of every clinical teacher I know.”

[SIDEBAR: Clinics Across Borders]

Guggenheim succeeded Amsterdam as director of Clinical and Advocacy Programs in 1988. He is particularly proud of his faculty recruiting and the expansion of clinic course offerings during his 14-year tenure. He inherited a distinguished group of mostly New York-based faculty, and created a more diverse faculty with a national reputation. The leading lights of this generation included Gerald López, who founded his own community-based law office in Los Angeles and subsequently taught public-interest law at the law schools of Stanford and UCLA; Anthony Thompson, a deputy public defender in California; Kim Taylor-Thompson, a former director of the Public Defender Service for the District of Columbia and Stanford professor, and Bryan Stevenson, who gained national prominence by appealing death-penalty convictions in the South.

The line-up of clinics also became more diverse. Professor of Clinical Law Sarah Burns, former legal director of the NOW Legal Defense and Education Fund, started the first nonlitigationfocused clinic, the Public Advocacy Clinic. It is cotaught with Brennan Center lawyers and has become the Brennan Center Public Policy Advocacy Clinic, designed to teach public policy reform strategies. López, a professor of clinical law, began the Community Outreach, Education and Organizing Clinic, in which students learn how to supplement traditional practice with a three-pronged problem-solving approach to helping the poor and educating the public about legal issues of the poor. Professor of Clinical Law Nancy Morawetz (with Michael Wishnie, who is now a professor at Yale Law School) began the Immigrant Rights Clinic (see “Come In and Get Out” on page 30), initially focusing on the rights of low-wage immigrant workers and protecting long-term lawful permanent residents from detention and deportation due to a criminal offense. Taylor-Thompson, a professor of clinical law, began the Community Defender Clinic, which teaches students to explore ways for defender offices to reinvent themselves and assume a broader role in the criminal-justice community by engaging in community outreach, building coalitions and participating in community action, and employing a wide variety of litigative and nonlitigative strategies, including legislative advocacy, community education, and media campaigns. Thompson, a professor of clinical law, launched the Offender Reentry Clinic (see “Beyond Law & Order” on page 23), which teaches students to be advocates for ex-offenders as they encounter legal and societal issues upon their return to free society, and Stevenson, a professor of clinical law, launched NYU’s nationally known Capital Defender– Alabama Clinic, which appeals death-penalty convictions in a state with no state public-defender system and 190 death-row inmates, 95 percent of whom can’t afford representation. When New York State reinstated the death penalty in 1995, NYU created the Capital Defender–New York Clinic, tapping Amsterdam (with, originally, Randy Hertz) and Deborah Fins, an attorney with the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, to teach it.

A 21st-Century Legal Education

Randy Hertz, who became director of the Clinical and Advocacy Programs in 2002, traces his interest in public-interest law and clinical education to his early life experience. As a high school student, he spent a summer as an intern for Queens Legal Services, standing on welfare lines with legal services clients. During college, he took a class with the late Democratic senator and social-justice champion Paul Wellstone, and worked with him in a community-based welfare rights organization. “The injustices that I saw and learned about made me feel like I had to devote my career and my life to trying to help those in need. It seemed to me that the best way to make a difference in the world would be to get a law degree and to devote my career to public-interest law.”

After Stanford Law School, where he had taken a criminal-law clinic taught by Anthony Amsterdam, Hertz joined the D.C. Public Defender Service, and then the NYU clinical faculty, teaching the Juvenile Defender Clinic. “All along the way, I had role models— people such as Amsterdam, Wellstone, and a Legal Aid lawyer named Neil Mickenberg,” he recalls. “They helped me to understand the critical importance of empathizing with clients, collaborating with clients, and seeking to empower clients. These are some of the lessons that I seek to pass on to my students.”

[SIDEBAR: Respecting the Family Order]

Indeed, Hertz serves as a mentor to many current and former students. In 2006, Juvenile Defender Clinic veterans Susan Lee ’06 and Vanita Gupta ’01 worked on a trial together in Louisiana in which they unexpectedly needed to cite a case in support of their argument that a defendant should be allowed to use statements that defense attorneys had previously succeeded in suppressing. They tried to access Westlaw from an Internet cafe during recess, but having no luck, they called Hertz, who gave them three cases in five minutes. “Maybe he doesn’t want this to get out, but students use him as a resource long after they leave the Law School,” says Lee.

The rewards of assuming that mentoring role are great. “Some of the best moments in clinical teaching are when students connect to their juvenile clients and bridge the divides that sometimes result from differences in race or class or by the lawyer’s professional status,” he says. “The student’s act of transcending that gap can make a crucial difference in helping a client overcome adversity in his or her life or in winning a case in court for the client.”

Hertz recounts the case of a 15-year-old client who was charged with robbery, but who claimed that he had acted under duress by other youths. “The case seemed unwinnable,” he says. “But clinic student Marisa Demeo ’93 won the bench trial by using witness examinations and closing arguments to help the judge see the world through the client’s eyes—to appreciate how peer pressure and fear could cause a young person to act in ways that would seem unreasonable to an adult.” Demeo was recently appointed a magistrate judge in the Superior Court of the District of Columbia.

Hertz lectures regularly to the local bench and bar about developments in criminal and juvenile law, and does pro bono work on briefs in criminal appeals, including capital appeals and habeas corpus proceedings. He is coauthor (with Amsterdam and Guggenheim) of the standard trial manual on juvenile court practice, and cowrote Federal Habeas Corpus Practice and Procedure.

All told, the Law School has 15 full-time clinical faculty, including 12 tenured or tenure-track faculty—the largest among top-five law schools. About half of all students take at least one fieldwork clinic before graduating—in 2006-07 about 325 upperclass students participated in 25 fieldwork clinics. The clinics have evolved, but the basic structure of the program has remained the same over the last two decades. Through lawyering classes, simulations and fieldwork clinics, students learn how to navigate the client-counsel relationship and test legal strategies. They see firsthand how the legal system works, and gain the tools, experience and insight to discover in themselves how to advocate for their clients. “Clinic was my biggest learning experience in law school,” says Bunton, the New Orleans juvenile defender. “There was, all of a sudden, this space where theory got applied to reality. Everything I had learned about how to practice came together. And then I understood why people call it the practice of law. No one really gets it right every time. It’s constant practice and constant learning.”

Hertz has expanded the clinical program in directions that serve the global community and redefine the nature of public-interest law. Both domestic and international clinics increasingly welcome collaboration with other fields, ranging from social work to medicine. “These changes all reflect trends in the world of practice,” says Hertz. “The clinical program adjusts to new developments by offering students a chance to learn about cutting-edge issues and interesting new approaches.”

One of the newest clinics, the innovative Medical-Legal Advocacy Clinic taught by Clinical Professor of Law Paula Galowitz, is a case-in-point. Students in the clinic, the first of its kind in the New York area, work with social pediatric medical residents at Montefiore Comprehensive Health Care Center, a federally funded community health center in the South Bronx, to develop and practice more holistic approaches to client treatment. Students handle legal issues that affect the health of the center’s patients, most from indigent African-American and Latino communities. The clients’ ailments include asthma triggered by mold from leaky roofs or rodent infestation and lead poisoning from paint.

Clinics continue to stretch beyond the role of teaching students how to litigate. The Mediation Clinic, taught by Burns and Ray Kramer, an administrative law judge with the Office of Administrative Hearings and Trials, begins by teaching students to resolve residence disputes in NYU dormitories and advances to mediating employment disputes arising at New York-area agencies. Galowitz will coteach the new Neighborhood Institutions Clinic with David Colodny, an attorney at the Urban Justice Center (UJC). The clinic will provide legal services to grassroots organizations that are clients of the Community Development Project of the UJC. The transactional needs of such organizations may include assistance with forming and governing a nonprofit, applying for tax-exempt status and negotiating leases.

The Comparative Clinical Justice Clinic crosses both geographic and theoretical borders. It’s taught by Professor of Clinical Law Holly Maguigan, an expert on legal issues affecting battered women who have killed or harmed their abusers, or who were coerced by their partners into committing crimes, and social worker and psychologist Shamita Das Dasgupta, the cofounder of Manavi, an organization committed to ending domestic violence against South Asian women living in the United States. Students examine how different nations combat domestic violence through criminal law; they also help develop new criminal-justice initiatives with U.N. agencies, advocacy groups and nonprofit organizations.

The clinical faculty has taken on an even deeper international flavor with the 2003 hires of Assistant Professors of Clinical Law Smita Narula and Margaret Satterthwaite ’99, whose credentials include advocacy and activism with Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International. (See “Clinics Beyond Borders” on page 26.) Coteaching the International Human Rights Clinic, Narula and Satterthwaite work together with their students to influence worldwide human rights policies through reports to Congress and the United Nations, and public-awareness campaigns on topics such as torture and racial profiling of Muslims, caste discrimination in South Asia, and lack of sustainable living conditions in Haiti.

Meanwhile, the long-standing clinics have evolved to adapt to changes in practice and new pedagogy. For example, the Civil Rights Clinic, taught for many years by Clinical Professors of Law Claudia Angelos and Laura Sager, has developed into two clinics that focus on cutting-edge civil rights issues. Sager teaches the Employment and Housing Discrimination Clinic, where students represent plaintiffs in discrimination cases in state and federal court. Angelos works with New York Civil Liberties Union attorneys Christopher Dunn and Corey Stoughton in a reconfigured Civil Rights Clinic on a wide range of civil liberties issues, including free speech, religious freedom and racial and economic justice. The Urban Law Clinic, taught for years by former Clinical Professor of Law Lynn Martell and Galowitz, evolved into the Civil Legal Services Clinic, focusing on housing and government benefits, and thereafter added a substantial component on representing clients applying for asylum.

A clinic that will be offered for the first time is the Supreme Court Litigation Clinic, taught by Dwight D. Opperman Professor of Law Samuel Estreicher with two adjunct professors who are partners at Jones, Day: Donald Ayer, a former U.S. deputy attorney general, and Meir Feder. The clinic will supervise students as they draft briefs and petitions for certiorari and oppositions. The clients will be prisoners appealing their convictions or seeking affirmative relief through civil actions. Students will take part in discussions with counsel and in moot courts and attend oral arguments.

Changing Views on Legal Education

Randy Hertz was a consultant to the task force that produced the 1992 MacCrate Report on legal education for the American Bar Association. The two-year study recognized the valuable contribution that clinics can make to a law school education, leading to a national discussion on legal education and pedagogy that continues today. In fact, Hertz recently lectured on his work on the report to students and faculty at three law schools in Japan. The country’s Justice System Reform Council is focusing on the role that clinical legal education should play in Japan’s law schools.

[SIDEBAR: Come In and Get Out]

The invitation to give those lectures is one more sign that, as in the 1960s, different forces—including 9/11 and its aftermath, the growing need for lawyers to represent those who have fallen through the widening holes in our social net, and increasing interest in clinical education here and abroad—are giving rise to a new era in clinical education. Hertz cites the 2007 Carnegie Foundation report, as well as the Clinical Legal Education Association’s recent Best Practices for Legal Education, as strong signs that clinical education is once again attracting the interest of the legal establishment and the broader legal community. Both advocate that law schools direct more resources to clinical programs in the education of law students, so that graduates are more adequately prepared for reallife practice early in their careers. The American Bar Association’s Section of Legal Education and Admissions to the Bar hosted a national conclave in May that brought together judges, lawyers and legal educators to discuss possible legal education reforms. “This is a very exciting time to be a clinical teacher,” says Hertz, who became chairelect of the ABA section in August. “We’re on the brink of developing and integrating important new ideas into clinical pedagogy to fulfill law schools’ responsibility to—as it’s phrased in the ABA Accreditation Standards for Law Schools—prepare students for ‘effective and responsible participation in the legal profession.’”

Hertz currently is the editor-in-chief of the Clinical Law Review, the only peer-edited journal of lawyering and clinical legal education, established in 1994. NYU cosponsors the journal with the Clinical Legal Education Association and the Association of American Law Schools. A recent issue featured an article by students, in collaboration with professors Amsterdam and Hertz, which examined the first Rodney King assault trial. Among other things, the piece explains how lawyers used narrative in litigation, describing the facts of the case, the procedural posture at the outset of the trial, and the “cultural surround” on which the lawyers were able to draw in crafting narratives that would likely resonate with the jurors. In 2006, Hertz helped organize the first-ever Clinical Law Review workshop, held at the Law School, which gave 60 clinical law teachers from across the nation a chance to focus on academic writing skills that can help them earn tenure—an increasingly important goal as clinical education gains a higher profile.

All of the attention to the training of clinicians and to the clinical curriculum, and serving communities in need, bear fruit in experiences like Rachel Meeropol’s. Meeropol ’02 is an alumna of Bryan Stevenson’s Capital Defender Clinic who now practices with the Center for Constitutional Rights in New York. She has acted as lead counsel on numerous prisoner rights cases, including Turkmen v. Ashcroft, a class-action suit on behalf of Arab and Muslim men rounded up in immigration sweeps after 9/11; Doe v. Bush, seeking representation for the unnamed detainees at Guantánamo, and other Guantánamo-related litigation. The American Lawyer recently ranked her among the 50 Top Lawyers Under 45. “We face some incredibly difficult battles in the field of immigrant rights,” she says. “Because of my clinic work, I’m less inclined to fear that battle, or view it as impossible to win.”

—Clint Willis has published more than 40 books, including award-winning anthologies on adventure, politics, religion and war. His writing has appeared in Money, Outside and the New York Times. Suzanne Barlyn has contributed to the Wall Street Journal and Fortune and is a non-practicing attorney who received her J.D. from American University Washington College of Law.

—Editor’s note: Since this article was published in September 2007, Alina Das ’05 has joined the NYU Law faculty; she co-directs the Immigrant Rights Clinic.