Fostering Justice

Inspired by her own parents’ service to the city of New York, Karen Freedman ’80 built a formidable organization to give kids in crisis a fighting chance.

Printer Friendly VersionOne morning last year, Karen Freedman ’80 took a short walk from her offices on Lafayette Street in lower Manhattan to the white granite fortress that is the Manhattan Family Court. Freedman is the unassuming yet powerful executive director of Lawyers For Children (LFC), and her history with the court spans 30 years and thousands of proceedings. On this day, she peeked in on a juvenile hearing in progress. What she saw made the calm and steady Freedman, in her own words, “absolutely crazy.”

A teenage girl, clenching her lawyer’s business card between her teeth, stood with her hands shackled behind her back.

The scene set off Freedman’s highly attuned sense of injustice. Who handcuffs children? It was degrading, inhumane, and unconstitutional—and occurring in front of her eyes. Still, as always, Freedman turned indignation into strategy.

After the hearing, Freedman launched an investigation. She asked the girl’s attorney about the handcuffs; surveyed her staff of some 65 other lawyers and social workers; and called the head of another Manhattan nonprofit, the Center for Family Representation (CFR), to ask whether their clients, many of them teen parents, were being routinely manacled.

A bigger picture came into focus. Court officers who escorted teens charged with minor offenses from criminal to family court kept them in handcuffs during child welfare hearings. Everyone in the courthouse had become inured to the sight of children standing in manacles throughout their proceedings, Freedman learned.

Under the law, every litigant is entitled to be free of restraints unless they present a danger of violence to themselves or others. In Manhattan—and in no other family court in New York City—that presumption had been flipped on its head. The Lawyers For Children client had faced a marijuana charge, hardly a violent offense.

Freedman sent a demand letter to the New York Office of Court Administration, the administrative arm of the state court system, which also happens to be the source of most of her agency’s funding.

The office agreed that handcuffing children had to stop. Freedman’s lawyers began to demand that their nonviolent clients be free of restraints. Still, nearly a year later, the practice continued.

“It’s like pushing against Jell-O,” says Freedman, seated in her big-windowed, award-filled corner office that looks out onto the Tombs, as the Manhattan Detention Complex is known. “No one will say that this should be happening. They say, ‘You’re absolutely right!’ And then nothing changes.”

Nothing changes, that is, until Freedman grabs hold.

MICRO AND MACRO

There, in microcosm, is Freedman’s modus operandi. First comes her empathic connection to a child, which often triggers her intuitive sense about a social injustice on a large scale. She investigates and finds allies, then outlines a list of demands. These are her first steps before taking legal action (if necessary) toward reform. Most effectively, perhaps, Freedman persists—without bombast or bullying—until she gets what she wants.

In this way, Freedman has wielded her New York University law degree as a sword for the public good: to improve, vastly, the lives of mostly poor children in foster care in New York City. If, at 60, she is as deceptively mild-mannered as Clark Kent, she is also as apparently mighty as his alter ego. Like the superhero, she is a merger of opposite traits: low-key and take-charge; steady and passionate; creative and rational; self-effacing and wickedly smart.

“There’s something so centered and focused and powerful within her,” says Vaughn Williams, an LFC board member. “And it’s an interesting dichotomy, because in a polite way she’s very tough. She’s motherly and sensitive to the kids that she’s representing, but then she’s also demanding and businesslike as a lawyer. And she has taken such a solid, consistent path, year after year, in an upward trajectory.”

The result is a New York City foster care system that is “way way better,” according to Martin Guggenheim ’71, Fiorello LaGuardia Professor of Clinical Law and a mentor of Freedman’s. “It’s a mindboggling success story.”

In addition to representing some 50,000 children in court over three decades, LFC has filed scores of class action lawsuits and appeals, almost always winning. It has shone a light on many subsets of aggrieved foster children, from those who witness domestic violence to older teens aging out of foster care to immigrants, sexual abuse survivors, and, most recently, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning youth.

And, from her start in 1984 with a team of two and a donated office, Freedman has built a nonprofit firm with a $7 million annual budget—almost $2 million raised privately—in a warren of offices on three floors. She exemplifies “how a lawyer wanting to do something different and entrepreneurial and outside the mainstream of big law can build an institution,” says Williams, former partner and now of counsel at Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom.

The surprising power of that institution derives, in part, from its ability to succeed at its micro and macro missions: helping children personally while formulating public policy. Freedman’s work rests on the proposition that every child deserves a voice. Toward that end, every client at LFC is assigned a lawyer as well as a social worker, so that a trained professional examines every facet of a child’s life. Relationships form and deepen. By the time the court hearing arrives, children are presented as fully dimensional people, not as cardboard cutouts of foster kids.

“Her lawyers stand out,” says former Family Court Judge Jody Adams, now special adviser to the commissioner of the Department of Homeless Services for Children and Families in Shelter. “They’re really smart, they know the law, and they know their clients. And her social workers are equally brilliant. They often brought older children into the court who then expressed themselves to me. I came to see their clients as individuals.”

LFC’s young clients, in turn, serve as experts on foster care. They are eyewitnesses to a system that has left them in violent homes, removed them from loving families, and often attempted to discard them as they entered adulthood—alone, jobless, and homeless.

Freedman’s gift is to listen to their voices and discern trends in everyday accounts. Then she goes to work at the very top of the child welfare food chain, meeting with commissioners she has known for decades, enlisting the aid of family and state court judges who respect her work, tapping New York’s prestigious law firms to lend their name—and letterhead—to particular fights.

ESCAPE FROM RIKERS

If a single client comes to mind for Freedman, it is Darren Martin. A brilliant student, Martin began to slip academically in 1996, when he was 15. He would threaten his classmates, and ravenously eat two free school lunches a day. Soon, his school’s dean learned that Martin’s mother had abandoned him for her boyfriends. He had been living alone in their Harlem apartment with no money and no food for three weeks.

The city’s child welfare agency, the Administration for Children’s Services, offered Martin some unappealing choices, including living in a group home—“That’s like dumping you in jail,” Martin says—or moving in with his sister in Baltimore. “The City of New York was just thinking of the quickest and easiest solution to get me off of their rolls. They clearly wanted to ship me away.”

A caring teacher called LFC, and Martin met with his new social worker and lawyer. “I felt understood,” says Martin, who told his team that his top priority was his education. “For how angry I was, I needed someone to redistribute and articulate those feelings into something else.”

Martin was placed in “kinship foster care” with an aunt and uncle, allowing him to complete high school. But two days after graduation, his foster parents handed him a plane ticket to Wisconsin; he was to enroll that fall at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. Until then, he had nowhere to live. “They’re kicking me out of the house and I have nowhere to go,” Martin told his LFC attorney.

It may as well have been the lament of every young adult who aged out of foster care in New York City, especially those placed in care voluntarily by parents who don’t want them. Young adults like Martin were cast adrift without an anchor to face adulthoods as bleak as those in a modern-day Dickens novel—of homelessness, prostitution, drugs, prison, or early pregnancy. One New York City study found that youths formerly in care comprised roughly one-quarter of the city’s homeless shelter population.

For Freedman, Martin’s case crystallized the aging-out crisis. With Legal Aid as co-counsel, she began negotiating with New York City to stop discharging foster youths into homelessness. The result, in 2011, was a sweeping court-ordered class-action settlement mandating that all foster children be released to stable housing and provided connections to jobs, further education, and at least one caring adult when they age out of the system.

In addition, Freedman led the creation of a special court, within New York City Family Court, whose sole job is to work with and track closely the well-being of foster children from age 18 until 21.

“These kids were in very bad shape,” says Douglas Hoffman ’81, supervising judge of New York County Family Court. “Karen suggested a radical change. She proposed a court that could be a model nationally. We’re still tweaking it, but it’s really a turnaround from A to Z.”

As for Martin, LFC negotiated with New York City to pay for summer housing and Martin boarded the plane to Madison, where he enrolled in a pre-college program until the fall. He graduated, then earned a master’s degree, married, and became a father. Today, at 33, Martin serves as the student services coordinator in the financial aid office of the University of Wisconsin–Madison.

“If I had been fending for myself,” says Martin, “I probably would’ve been that angry black teenager who ended up at Rikers.”

DO-GOOD DNA

Freedman, an NYU School of Law trustee, is well aware of the distance between her usually penniless clients and her own privileged origins in New York City.

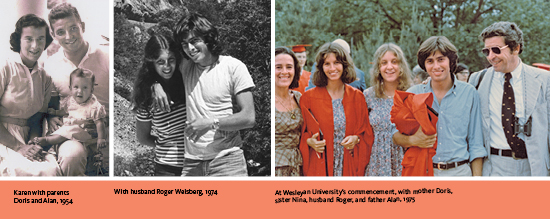

Freedman’s energetic mother, Doris, was a crusader for art and artists. She presided over the Municipal Art Society, a private organization dedicated to landmarks preservation and New York City’s building landscape, and founded the Public Art Fund, a non-profit organization dedicated to mounting contemporary art in the city’s public spaces. A plaque and named plaza at the southeast corner of Central Park honor her legacy. Freedman’s father, Alan, a businessman, founded the WNYC Foundation to increase private funding for public radio.

In Karen’s early teens, her family moved into the Century building on Central Park West. It was designed and built by Freedman’s maternal grandfather, Irwin Chanin, a New York City architect responsible for many of New York’s jazziest Art Deco buildings, as well as half a dozen Broadway theaters. The Irwin S. Chanin School of Architecture at Cooper Union memorializes his work.

In 1969, not long after that move, the New York Times published a feature showcasing the work and home of Doris, who had become New York City’s first director of cultural affairs. The story, “Even Buying Art Is a Democratic Process in Freedman Home,” peered into the Freedmans’ life, suggesting facets of wealth and influence that, Freedman says, told only part of her family’s story.

Alan had grown up modestly in Brooklyn and Cleveland. He joined the Air Force, and afterward went to work rather than college to support his young family. He began selling advertising for a small New Jersey company that made desk accessories and marine instruments, working his way up steadily to become president. All along the way, Doris and Alan Freedman insisted on raising their family on their own earnings.

Freedman modeled her parents’ dedication to work. In 1970, she took a job as a counselor at Camp Ramapo for Children, in Rhinebeck, New York, for kids with emotional and social disabilities. The experience would deeply affect her and influence the course of her life.

“Most of the campers were inner-city kids,” says Freedman, who is petite and speaks in a thoughtful cadence, without “ums” or “uhs.”

The camp philosophy then was to hire counselors close in age to the campers. Freedman, at 16, had the charge of a cabin of 15-year-olds, a practice she now thinks of as “insane” and legally suspect. Yet it opened her eyes.

“It was transformative,” she says. “I loved working with kids. I felt energized by them. They were difficult, complicated, tough kids, but that’s what I knew I wanted to do. I didn’t know how, I didn’t know in what form, but I knew that going forward in my life I wanted to work with children.”

The very idea of making a difference had been cultivated during Freedman’s formative years at the progressive Ethical Culture Fieldston School, with its emphasis on social justice. The school’s charge is not to teach students to adapt to the existing social order, but rather “to change their environment to greater conformity with moral ideals.” Three generations of Freedmans are graduates.

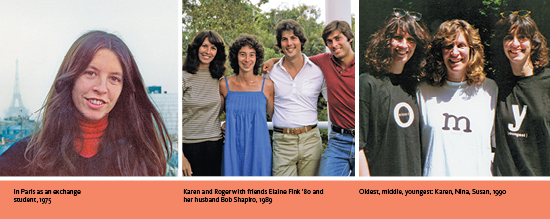

She found similar values at Wesleyan University, where she graduated summa cum laude, and where she met her husband, Roger Weisberg, a documentary filmmaker, whose work on social justice issues often dovetails with Freedman’s. In a highly competitive field of boosters, Weisberg says he is his wife’s greatest. He fell, in part, for her “selflessness and compassion.” He admires how she has given voice to children. He respects Freedman’s agility as both adversary and ally. “She can collaborate with the very people she’s dragging to court to force a reform,” he says.

After college, Freedman went to work in the Manhattan District Attorney’s Office, where she came to appreciate the power of the law. She decided on law school. “I felt that law school would allow me the greatest opportunity to advocate on behalf of individual children and make positive systemic change,” says Freedman. “That was the trajectory that I wanted to follow.”

That clarity of thought and purpose led her to become a Root- Tilden Scholar. In 1977, Freedman was one of about 20 NYU Law students selected for the program, which encourages careers in public service and public interest law. At the scholars’ first meetand- greet, Freedman befriended Elaine Fink ’80.

“I was taken with her,” says Fink, who is the managing attorney for children’s advocacy at the Legal Aid Society of Southwest Ohio. “The way she talked about her work touched me and intrigued me. We both knew we weren’t competing for the best law firm job out there. We had lofty, improve-the-world goals.”

At NYU, Professor Guggenheim’s seminar on Children and the Law began to shape Freedman’s thinking. In his scholarship, Guggenheim has examined the unwitting harm that can occur when lawyers represent children. Under the banner of children’s rights, he argues, lawyers for children often create antagonisms with parents, resulting in more broken families and more children harmed in foster care.

Freedman considers Guggenheim her most influential mentor and, at times, her most formidable ideological adversary.

“The notion of an attorney acting in the ‘best interests of the child’ can be used to cause great harm and detriment to children,” Freedman says. “That is why at Lawyers For Children the voice of the child is paramount. There is a social worker and a lawyer assigned to advocate for every child, and in those circumstances where a child is developmentally incapable of comprehending and participating in the court proceedings, it is the skilled social worker who will use substituted judgment to help the attorney formulate the legal strategy on that case.”

But before graduating from law school, Freedman faced a series of devastating family losses. In 1979, her mother underwent routine surgery. In recovery, she stopped breathing and lapsed into a coma from which she never recovered. Two years later she died, at 53. Doris’s passing was followed little more than a year later by Alan’s death from a heart attack. He was 58.

Eulogizing Alan for a New York Times obituary, Mayor Edward Koch ’48 said the Freedmans had performed “magnificent service” to the people of New York, leaving behind “monuments of spirit” to the city. They also left behind both inspiration and challenges for their three daughters just as they were entering adulthood.

“We had a very, very close family,” says Freedman, “and there was this unwritten thought, amongst all three of us, that the way to honor our parents would be to carry on a legacy of giving that we saw them emulate for us.”

All three sisters have done so amply. Susan Freedman is the current president of the Public Art Fund. Nina Freedman is part of the Global Philanthropy and Employee Engagement team at Bloomberg. Karen Freedman assumed the role of matriarch, keeping the family glued together through years of loss and grief.

“Probably the hardest thing in having something like that happen to you when you’re relatively young—and I was in my early 20s and my youngest sister was just turning 20—is to try and ensure that you don’t go on living the rest of your life in the crash position, fearful and immobilized,” says Freedman. She wills herself instead “to face challenges and take risks and allow my own children to have the confidence, independence, and courage necessary to make a difference in the world.”

Her three children are on their own paths toward public service in art, medicine, and law. Allison Weisberg founded an interactive alternative art space in SoHo, Recess, where artists work while the public may observe and interact. Daniel Weisberg is in an internal medicine residency at Harvard, with a specialty in public health. Liza Weisberg may hew most closely to her mother’s line of work; she completed a two-year trial preparation assistant position at the Manhattan District Attorney’s office and has just begun her first year at Harvard Law School. “In the best possible way, she’s given me totally unreasonable expectations about what’s possible as a mother and a professional and a lawyer,” says Weisberg.

But a family joke reveals the extent of her mother’s caution. Departing Cuba at the end of a family vacation during which Allison stayed behind for a college exchange program, the family was battered by a heavy rainstorm. Freedman fretted about leaving Allison.

What could possibly harm her, a family member wondered aloud.

“I don’t know,” said Freedman. “She could get washed into a drainpipe?”

The drainpipe became code for Freedman’s awareness of her overprotective instincts, as in a text she might write to one of her children: “Are you home yet or are you in a drainpipe?

Then again, her protectiveness—of New York City’s foster care children—has been a life force.

THE MOST VULNERABLE

The colorful waiting area on the eighth floor of 110 Lafayette Street features a fanciful mural of an airplane flying through clouds, with the plane’s cockpit windows opening to the real receptionist’s window. A boy and a dog in a rowboat float alongside the plane, and a Lawyers For Children banner flaps in the wind.

The inviting décor underscores the youth-friendly, one-on-one services of the organization—perhaps the Clark Kent side of the operation—while in the offices beyond, Freedman and her staff use legal muscle to challenge wrongdoing on a large scale.

Recently, Freedman turned her attention to the crisis among LGBTQ youth, one of the most preyed-upon subsets of children in foster care. Lawsuits and academic reports chronicle the overrepresentation of LGBTQ youth in care—usually black and Latino—and how they suffer every imaginable abuse almost from the moment they come out to family: homophobic bullying, broken bones, sexual assault.

LFC has long had a project to support individual clients, but in early 2012, Freedman perceived an opportunity to make change on a larger scale. A client served as catalyst. He reported abuse and neglect at his group home, Green Chimneys Gramercy Residence, a nondescript brownstone in the East Village touted as a cutting-edge program for LGBTQ youth. “He was telling us of inappropriate sexual advances being made by staff members to the young people living there,” Freedman says. “He told us there was no viable programming, children were routinely locked out of the residence and left on the streets, food was scarce, and staff were clearly without adequate training—bullying, humiliating, and even abusing the young teens in their care.”

She contacted an old friend, Ronald Richter, who, under Mayor Michael Bloomberg, had been appointed commissioner of the Administration for Children’s Services. Richter was the city’s first openly gay child welfare commissioner, and, coming from a long career as a family court judge, was well acquainted with the miserable plight of LGBTQ youth in foster care. Freedman invited Richter, who is married and has a daughter, to LFC’s offices, where he heard stories from several of Lawyers For Children’s LGBTQ clients. “They felt incredibly validated, having that kind of access,” Freedman says.

Richter, in turn, was moved. “When you’re running a child welfare agency, everything is very, very important,” says Richter, who has since returned, under the new city administration, to his judgeship at Queens Family Court. “And there are only certain things that you can act upon with the force of a city agency. Karen made sure that this issue was acted upon with force.

Commissioner Richter himself made a series of unannounced visits to the Gramercy residence, and while he worked with the agency to remedy deficiencies with both the facilities and the services, he finally ended the contract. “We agreed to disagree about their ability to provide programming,” says Richter, “so there was a parting of ways.”

(Green Chimneys declined to comment on the Gramercy closing.)

Freedman pushed on. She enlisted LFC board member Williams, of counsel at Skadden. They co-signed a demand letter to Richter, outlining specific protections for LGBTQ youth. Williams’s presence in a series of meetings signaled Freedman’s intent to sue if change was not imminent.

Despite her longstanding friendship with Richter, she pressed him, demanding that the city vastly increase the number of safe placements for LGBTQ youth, and that it train and advocate up and down the chain of child welfare services.

“There’s no winning Karen over,” Richter says. “She’s never going to decide to favor something because she likes you, or you want her to. She’s true to herself and her core beliefs. Which, of course, can be very annoying. She has a ton of integrity.”

TURNING UP THE HEAT

Freedman’s agenda is never-ending. She has engaged professionals on her firm’s board to teach public speaking and self-presentation to a cadre of rotating “ambassadors” from among her 18- to 21-year-old clients. They will advocate on behalf of LFC, spread word of its programs to others, and learn how to best advocate for themselves in the process. And she is determined to take the most cutting-edge research on brain science and apply it to New York City’s child welfare system.

“We have a system that’s about 30 years behind in terms of good practice,” says Freedman. Many agencies still use confrontational, behavior-modification methods on youths who carry traumas akin to those brought home by war veterans. And when agencies seek arrest warrants for AWOL youths, the result often triggers a negative spiral, she says. “It’s really an abuse of the entire police system,” Freedman adds.

Then there is the matter of the handcuffs. Freedman’s second demand letter elicited silence from the same state court office that awards LFC $5 million annually. Self-preservation might dictate backing down; Freedman, however, stepped up pressure. She tapped the prominent law firm Simpson Thacher & Bartlett, which sent yet one more letter. “It’s a way of strong-arming them,” Freedman says mildly. “It will get their attention.”

This summer, the wheels started turning. In a letter, the state court agreed to adopt new rules to remove handcuffs in family court “in a timely manner.” That may not end the practice. But if history serves, Freedman will win this contest. On matters of justice for children, she always does.

As sure as time goes on, the cuffs will come off.

—Candy J. Cooper, a Pulitzer Prize finalist, is a journalist and author living in Montclair, New Jersey.

—