A Tax Haven

Arthur Vanderbilt envisioned a formidable graduate tax program in 1945. Nearly 70 years later it remains the powerhouse platform for launching tax law careers in the nation’s top law firms and law schools, multinational corporations, and the US government.

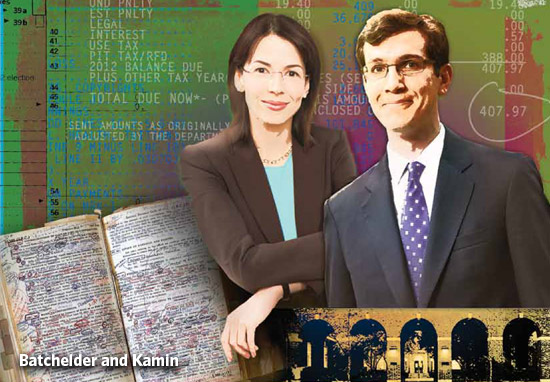

Printer Friendly VersionOn a cold Tuesday in January, David Kamin ’09, an assistant professor of law and the newest member of NYU Law’s tax faculty, was presenting a paper on the United States budget at the Law School’s Tax Policy Colloquium. Held in a classroom in Vanderbilt Hall, the colloquium nonetheless had the feel of a conference in Washington, DC: Among those in attendance were noted policymakers such as Peter Orszag, distinguished scholar at NYU Law and former director of the White House Office of Management and Budget (OMB), and William Gale, a prominent economist at the Brookings Institution. Students (who take the colloquium for credit) and academics made up the rest of the audience.

Under discussion was a 2012 paper, “Are We There Yet?: On a Path to Closing America’s Long-Run Deficit,” that Kamin wrote for Tax Notes, a popular tax news and commentary magazine. The deficit discussion, with tussles over tax increases and spending cuts, was one of the biggest and most important political battles in Washington, and Kamin—who at the age of 33 is one of the country’s top experts on the federal budget—thought that the common wisdom was wrong.

The Congressional Budget Office’s projections showed a longterm budget gap of nearly nine percent of GDP over the next 75 years. The impact: Stabilizing the country’s debt-to-GDP ratio would require a combination of $1.3 trillion in spending cuts and revenue increases per year, starting immediately and growing with the economy. The size of those numbers had Washington in a tizzy.

Kamin argued that uncertainty and flawed predictions, including a failure to include consensus measures on which Republicans and Democrats agreed or to account for what he called a “long game on revenue”—meaning those tax provisions already in place that will bring in more funds in future years—gave a false impression of how bad things were. The actual long-term gap could be below two percent, he said, an amount that would be hard to categorize as a crisis. “[D]enying the possible progress distorts the policymaking process and does not reward tough choices when they are made—while also justifying evermore radical solutions,” he wrote.

That provocative argument is exactly the kind of thinking for which Kamin is known, and why the school wooed him back. Kamin, until last year an economic adviser to the OMB and the National Economic Council, and Lily Batchelder, on leave to be chief tax counsel for the Senate Finance Committee, embody tax law’s trend toward innovation. At a time when fiscal policy is splashed on the front pages of every newspaper, they both influence the national debate and form a bridge between Washington and the Law School classrooms.

They join other NYU Law faculty with a tax policy focus, including Daniel Shaviro, organizer of the Tax Policy Colloquium and one of the nation’s leading tax policy academics; Deborah Schenk LLM ’76, editor-in-chief of the policy-focused Tax Law Review; Joshua Blank LLM ’07, who specializes in tax administration and compliance; and Mitchell Kane, whose interests lie at the intersection of tax with environmental policy and development economics.

The tax faculty also encompasses those who focus on cutting edge transactional tax issues, such as Noël Cunningham LLM ’75, a foremost authority on the taxation of partnerships; Leo Schmolka LLM ’71, an expert in estates and partnerships; Laurie Malman ’71, who specializes in individual and corporate tax; John Steines LLM ’78, who focuses on corporate and international taxation; and Brookes Billman LLM ’75, an expert in tax procedure. In addition, top practitioners such as Victor Zonana ’64, LLM ’66 in hot areas like taxation of cross-border transactions also teach as adjuncts. This combined focus on both policy and practice makes NYU Law—whose tax law curriculum has been ranked number one by U.S. News & World Report every year since the survey began in 1992—“home to a world-class tax faculty that has a deep impact on national, and often global, tax policy debates,” says Blank, faculty director of the Graduate Tax Program.

The tax faculty also encompasses those who focus on cutting edge transactional tax issues, such as Noël Cunningham LLM ’75, a foremost authority on the taxation of partnerships; Leo Schmolka LLM ’71, an expert in estates and partnerships; Laurie Malman ’71, who specializes in individual and corporate tax; John Steines LLM ’78, who focuses on corporate and international taxation; and Brookes Billman LLM ’75, an expert in tax procedure. In addition, top practitioners such as Victor Zonana ’64, LLM ’66 in hot areas like taxation of cross-border transactions also teach as adjuncts. This combined focus on both policy and practice makes NYU Law—whose tax law curriculum has been ranked number one by U.S. News & World Report every year since the survey began in 1992—“home to a world-class tax faculty that has a deep impact on national, and often global, tax policy debates,” says Blank, faculty director of the Graduate Tax Program.

At law schools across the country, there has been a shift from practice to policy, especially in tax. The tax code itself is arcane and complex, and tax lawyers can spend years of study deep in its details to learn to navigate it for their clients. But the rules and regulations that govern this country’s tax policy are also an expression of who we are as a people and what social policies we want to foster or curtail. Should the tax law be used to shrink poverty? Can it be tailored to ease inequality? In a global economy, what is the best way to tax US-based multinational companies? Should investment income be taxed at lower rates than wage income? Should an estate tax or inheritance tax halt family dynasty-building? Should the tax law be used to change our behavior, such as by encouraging us to purchase health insurance? Whatever your political perspective, the questions multiply the more you try to get your arms around them.

Nowhere does this increased emphasis on tax policy find a more organic fit than at NYU Law. “I think it’s a natural extension of the fact that the school is focused on public service,” says Batchelder. “One of the things you can do is be a public interest lawyer and have clients, and another thing you can do is work on policy issues.”

“The most complete and imaginative offering”

The federal income tax was passed into law 100 years ago, in 1913, and for the first few decades of its existence law students learned about tax as a minor offshoot of constitutional law. “Tax as a subject came into the curriculums of law schools in the 1930s,” says M. Carr Ferguson LLM ’60, a longtime member of the tax faculty and former US assistant attorney general for the Tax Division of the Department of Justice, who now teaches as an adjunct. “It was regarded as the work of accountants until then.”

It wasn’t until 1934 that Randolph Paul ’13—one of the name partners of Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison—co-wrote the six-volume Law of Federal Income Taxation, one of the earliest studies of tax as a legal discipline. And while taxation had become more complicated by the 1940s, and litigation had begun to build up case law, law schools had not kept pace with the developments.

That was the landscape when Arthur Vanderbilt became dean of NYU School of Law in 1943 and quickly moved to enhance the school’s reputation beyond its regional base. Tax, Vanderbilt realized, was a wide-open area for training lawyers, and teaching it could give NYU an edge in the new field. While NYU Law offered a couple of basic tax courses then, there were no professors who specialized exclusively in tax. Vanderbilt’s idea would go one giant step further than simply beefing up the tax curriculum for JD students; he would establish a graduate tax program, the first in the nation, and create an academic home for all those who cared about tax. “It was a radical departure in legal education,” says Professor Emeritus John Peschel, who joined the tax faculty in 1967.

To make a splash with this new program, Vanderbilt was determined to hire Gerald (Jerry) Wallace, one of the country’s most brilliant tax teachers. Wallace had taught at Yale and had worked as special assistant to the US Attorney General and as chief of the criminal unit of the Justice Department’s tax division. Vanderbilt convinced Wallace to leave Cravath, Swaine & Moore in 1945.

Wallace was not only one of the nation’s most beloved tax professors, but he had also devised a new way of teaching tax that replaced law schools’ traditional Socratic method. In the problem method, as Wallace’s way came to be known, students were given a set of facts and required to analyze the code, regulations, and case law to produce an answer. This allowed students to get deep into the tax code and grounded the analysis with real-life problems and rules, rather than getting into a discourse that might veer too far into the hypothetical. Students across the country are now taught tax with the problem method. This, Schenk says, is in part because NYU has educated so many tax law academics.

The program launched with evening courses for associates at the city’s elite firms who were seeking LLMs. Wallace, known as the Chief and renowned for the camaraderie he fostered, built up the curriculum and expanded the program, teaching at NYU until 1983. Eventually, the program grew to offer a full-time day schedule.

Senior members of the tax faculty still tell stories about how the Chief and Charles Lyon—who joined the faculty in 1955 after serving as deputy chief prosecutor at the Nuremberg trials and being an early name partner at what became Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom—would hold court at Marta, a nearby Italian restaurant where Blue Hill is today, drinking martinis. (This was, after all, back in the day of the three-martini lunch.) Students would join them after class. “Charlie and Jerry would go there so regularly that their drinks would be ready at their table when they got in from their morning classes,” recalls Ferguson.

Wallace not only knew all of the program’s students, but he also remembered the names of their girlfriends and boyfriends. And Lyon, who was widely read—and was married to New Yorker writer Andy Logan—would make jokes. The duo also organized outings to Bear Mountain, basketball games, and other social events with the graduate tax students. “It was just the personalities of Jerry and Charlie. They were the kind of people who wanted to engage students,” says Stephen Gardner LLM ’65, a partner at Cooley and an adjunct professor since 1966. “Jerry didn’t care about writing; it was not what he considered important.”

Vanderbilt, who later became chief justice of the New Jersey Supreme Court, had big ambitions for the tax program, and he insisted on creating a new law review that would be the first such journal devoted exclusively to taxation. The Tax Law Review, which remains the preeminent tax law journal, launched in 1946.

As Dean Russell Niles wrote in a commemoration of his predecessor, Vanderbilt, in the Tax Law Review: “Vanderbilt was not a tax lawyer; he did not even find the study of tax law congenial. As an imaginative realist, however, he saw before any other law school dean what the impact of the new tax laws would be on the post-war world…. And so, with his usual audacity and vigor, he recruited a tax law faculty…and with their help set up the most complete and imaginative offering ever made in this field.”

As the program gained in students and popularity, NYU Law brought in heavy-hitting tax lawyers to join Wallace and Lyon in teaching there. James Eustice LLM ’58, known to all lawyers for his co-authorship with Boris Bittker of the most important corporate tax treatise, Federal Income Taxation of Corporations and Shareholders, arrived at NYU Law in 1960.

Eustice, who died in 2011, was a marathon runner—known for wearing tracksuits and passing hours running around Washington Square Park—who kept stacks and stacks of paperwork (and of used Styrofoam coffee cups) in his office. Though his notes scribbled in the margins of the tax code were barely legible, and he never did use e-mail, his mind was a steel trap about all things tax-related. He had spent decades, after all, keeping B & E, the nickname for nothing less than the treatise on corporate tax law, up to date. “He was revered by everyone,” says Schenk. “If the answer was not in his book, there was no answer. He knew everything there was to know about tax.”

An expression of who we are as a people

As the Bush tax cuts approached their expiration at the end of 2012 and congressional Democrats and Republicans prepared for battle, Lily Batchelder was the woman at the center of the storm. On leave from her professorship of law and public policy at NYU Law since 2010, Batchelder has been the Senate Finance Committee’s chief tax counsel, serving as right-hand person to its powerful chairman, Senator Max Baucus, in the tax negotiations. In 2012, inside-the-Beltway newspaper Roll Callnamed her one of the top five Hill aides to know regarding tax and noted that she had become “a very visible presence on Capitol Hill, often appearing on the dais at hearings, and alongside [Baucus] as he roams the hallways.” She has led all of the committee’s tax work over the last couple of years, including the tax extensions and reauthorization of federal transportation programs.

Batchelder, whose low-key manner belies her sharp intellect, came to tax policy because of a passion for social justice and economic fairness. Unlike many tax professors who gravitate to tax early and have straightforward career paths, by the time Batchelder joined NYU Law in 2005 she had worked as a client advocate at a small social service agency in the Brownsville section of Brooklyn, as director of community affairs for then–State Senator Marty Markowitz (who’s now the Brooklyn borough president), and as a tax attorney at Skadden, Arps. She has both a master’s in public policy from Harvard University’s John F. Kennedy School of Government and a law degree from Yale Law School.

Batchelder’s academic interests naturally fall squarely at the intersection of tax and social policy. She has completed research on how to use tax incentives to help low- and middle-income families and how to structure wealth transfer taxes for societal good. “What interested me about both was, how can we promote equal opportunity so that people’s economic rewards reflect their efforts, and folks from disadvantaged backgrounds get a fair shot,” she says.

For example, Batchelder has been a big proponent of structuring financial incentives as refundable tax credits. The credits are available to people regardless of whether they owe income tax, and they are considered more progressive because the poorest families, who otherwise might be excluded from the benefit, can use them. (Most tax incentives, by contrast, are nonrefundable, which means taxpayers can take them only to reduce their tax bills.) “Why not give incentives to people that need them the most?” Batchelder asks.

Like most tax policy wonks, Batchelder is interested in ways to simplify the tax code. Consider, she says, the complexity of tax benefits for higher education; there are more than 10 credits and deductions, each with its own rules and eligibility requirements. “If we’re going to use the tax code to promote education, we should do so in the most cost-effective way,” she says. Equally important for the education benefits in an age when college costs have soared, she argues, is the issue of timing. Families that are really strapped for cash would do better to get the education benefit before paying tuition, rather than waiting to get money back on the next year’s tax return. “Maybe you could claim it based on your previous year’s income, or we could give it to the university,” Batchelder ponders. “How could we build it into the sticker price that prospective students are facing, rather than them having to build a spreadsheet to figure out what tax benefits they might be able to claim?”

Like most tax policy wonks, Batchelder is interested in ways to simplify the tax code. Consider, she says, the complexity of tax benefits for higher education; there are more than 10 credits and deductions, each with its own rules and eligibility requirements. “If we’re going to use the tax code to promote education, we should do so in the most cost-effective way,” she says. Equally important for the education benefits in an age when college costs have soared, she argues, is the issue of timing. Families that are really strapped for cash would do better to get the education benefit before paying tuition, rather than waiting to get money back on the next year’s tax return. “Maybe you could claim it based on your previous year’s income, or we could give it to the university,” Batchelder ponders. “How could we build it into the sticker price that prospective students are facing, rather than them having to build a spreadsheet to figure out what tax benefits they might be able to claim?”

A related issue, which Batchelder explored in a 2009 Tax Notes paper, “Estate Tax Reform: Issues and Options”—written as the federal estate tax was approaching its one-year disappearance in 2010—is changing the way we tax the transfer of wealth from one generation to the next. In her paper she argued that not only could the estate tax be improved, simplified, and potentially expanded, but it could also be replaced with an inheritance tax. (Don’t expect that to actually happen in Washington, where the year-end tax agreement kept the estate tax with a generous $5 million exclusion.) “What interested me about that was focusing on opportunity and privilege, and making sure people’s tax burden reflected how well off they were,” Batchelder says. “You might have two people earning $40,000, but one of them has a $4 million inheritance. That person is better off, but the tax code doesn’t differentiate.”

For Batchelder, her time at NYU has informed her work in Washington, just as she expects that her work for the Senate Finance Committee will affect her teaching and research when she returns. In Washington, for example, Batchelder has become used to talking about tax policy in lay terms—most congressmen and congresswomen, after all, don’t know the ins and outs of the tax code beyond their talking points—and she has become more pragmatic about the way tax law is actually created. “There are some provisions I would speak about in tax class with this attitude of ‘Why are they doing this? It’s the stupidest thing ever.’ I’ve learned that some of these things are more sophisticated than I would have thought,” she says. “And sometimes it does come down to trying to reach a deal with certain members of Congress. It may not be the perfect policy, but you do not want to make the perfect the enemy of the good.”

While Batchelder spent 2012–13 immersed in tax policy discussions in Washington, David Kamin—who had been Batchelder’s student and crossed paths with her in Washington—escaped the day-to-day grind of writing position papers in order to join the NYU Law faculty. “I really loved working on tax and budget policy for the Obama administration,” Kamin says. But after three and a half years, Kamin—who is married and has a young daughter—was ready for a change from the late nights and constant battles of fiscal policymaking. “I wanted to work on larger pieces, versus the memos and fact sheets that are the lifeblood of policymaking in DC,” he says. “I want to think on a larger scale.”

Kamin has a bachelor’s in economics and political science from Swarthmore College, and worked for the Committee for Economic Development and the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities before getting his JD magna cum laude at NYU Law. Even then, he was on the fast track: He became special assistant to Orszag, then the newly appointed director of the OMB, before even finishing his law degree. In a 2008 NYU Law Review article he wrote while still a student (that was excerpted in this magazine that year), “What Is a Progressive Tax Change?: Unmasking Hidden Values in Distributional Debates,” Kamin asked what it meant for a tax change to be considered progressive or regressive, concluding that measures of progressivity are often used in misleading or incoherent ways.

Kamin has a bachelor’s in economics and political science from Swarthmore College, and worked for the Committee for Economic Development and the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities before getting his JD magna cum laude at NYU Law. Even then, he was on the fast track: He became special assistant to Orszag, then the newly appointed director of the OMB, before even finishing his law degree. In a 2008 NYU Law Review article he wrote while still a student (that was excerpted in this magazine that year), “What Is a Progressive Tax Change?: Unmasking Hidden Values in Distributional Debates,” Kamin asked what it meant for a tax change to be considered progressive or regressive, concluding that measures of progressivity are often used in misleading or incoherent ways.

At the National Economic Council, as special assistant to the president for economic policy, Kamin made a significant impact on important policy legislation, including Obama’s healthcare law, the continuation of the payroll tax cut (through 2012), and the resolution of the debt crisis (in 2011).

Kamin is currently working on a Tax Law Review paper, “Poverty, Not Inequality: Federal Taxes and Redistribution,” about how the tax system cannot be used well to reduce inequality, though it can be used effectively to reduce poverty, and how pulling apart those two ideas can help create more effective policy. “If you look at the practical limits of the tax system, it is not going to have much impact on overall income tax distribution,” Kamin says. “But it can have much more effect on the welfare of people at the middle or bottom income levels. That’s different from inequality. If you distribute even a little to the bottom, it has a big impact.”

Another area of interest for Kamin is baselines, the seemingly simple concept of measuring where we are now that raises thorny policy questions. “In budget and tax, this creates a controversy: What’s a tax increase, and what’s a tax cut? Is what we agreed to [in the fiscal cliff deal] a $600 billion increase, or a $4 trillion tax cut?” Kamin asks. “If you look at the official score, it looks like a $4 trillion tax cut because the tax cuts were supposed to expire, but relative to current policy it’s a $600 billion tax increase.”

Kamin’s scholarship often shows how budget and tax metrics deeply influence policy debates, even as they are frequently misunderstood. He delves deep into the numbers to come up with original arguments that, typically, counter the conventional wisdom. Nowhere is this more true than with an idea he’s now exploring on the distributional impact of tax and spending policy. The common wisdom is that you can look at a tax bill and figure out its distributional impact—for example, that the Bush tax cuts benefited everyone but disproportionately benefited the wealthy. Kamin argues that because the common perception looks only at a particular time, it misses a bigger and more nuanced story. “Whenever you increase spending and cut taxes, you either have lower spending or higher taxes in the future,” Kamin explains. “In figuring out the actual effect, I can tell a plausible narrative that the end result of the Bush tax cuts is a tax system that is more progressive—however unintentional that may have been. At the same time, the tax system is producing less revenue, and that is now resulting in cuts to federal programs with regressive distributional consequences.”

The way Kamin sees it, part of the payback occurred in the year-end tax legislation, with the first major tax increase on high earners in 20 years (marginal tax rates for married couples making over $450,000 rose from 35 percent to 39.6 percent). Meanwhile, tax cuts which benefited all taxpayers but especially helped those at middle- and low-income levels, including the carving out of the 10 percent tax bracket, remained. The result: Over the long term, tax rates at the top of the income scale largely returned to their old levels, while tax rates at the bottom are lower. Programs like Head Start, however, are facing significant cuts due to fiscal pressures. “We now ironically have a more progressive tax system, but there are also less government services and a weaker safety net than would otherwise be the case,” Kamin says. “It may seem like splitting hairs, but it is a more accurate way to look at the net impact.”

In addition to his scholarship, Kamin is teaching a federal budget seminar, which he designed. And he hopes that he and Batchelder will be role models to students who are interested in the policy world. Tax lawyers, perhaps more so than others because of the technical expertise required, often create careers that span both private practice and government service. “Having Lily and me here will hopefully give people entrée into a different career path if they are interested,” Kamin says.

While he was in Washington, Kamin recalls, he would sometimes call Shaviro—his professor at NYU Law and one of the country’s top tax policy experts—to walk through some arcane analysis that he was struggling with. “Now I can just knock on his door,” Kamin says with a laugh. “For me, it’s been very exciting to be a student in the program and then come back to teach.”

While Batchelder and Kamin are relative newcomers to NYU Law, the shift from practice to policy has been underway for more than two decades, built up by longtime professors Schenk, Shaviro, and others.

Deborah Schenk, Ronald and Marilynn Grossman Professor of Taxation, was unusual in many ways when she joined the tax faculty 30 years ago. She was one of the first women (along with Laurie Malman) in a clubby, male environment, and the first woman tax professor to get tenure. She took charge of the quarterly Tax Law Review, and as editor-in-chief for the past 25 years has made it the foremost publication for tax policy research. And she has mentored hundreds of students, particularly those interested in becoming tax academics themselves, many of whom completed the acting assistant professor program.

Deborah Schenk, Ronald and Marilynn Grossman Professor of Taxation, was unusual in many ways when she joined the tax faculty 30 years ago. She was one of the first women (along with Laurie Malman) in a clubby, male environment, and the first woman tax professor to get tenure. She took charge of the quarterly Tax Law Review, and as editor-in-chief for the past 25 years has made it the foremost publication for tax policy research. And she has mentored hundreds of students, particularly those interested in becoming tax academics themselves, many of whom completed the acting assistant professor program.

“Deborah is the most amazing mentor. She tells it how she sees it,” says Sarah Lawsky LLM ’06, a professor at the University of California, Irvine, School of Law and an adjunct professor at NYU Law. “She’ll go to bat for you, but you have to live up to her standards. There are so many tax professors in this country who owe their jobs, and their work, to Deborah.”

Schenk’s own research runs the gamut, including a treatise on Subchapter S corporations and a number of pieces about low-income taxpayers and small businesses. Her article “Exploiting the Salience Bias in Designing Taxes” (Yale Journal on Regulation, 2011), for example, looked at the issue of salience—that is, things that are disclosed visibly—and how that relates to taxpayers’ cognitive biases. The idea of looking at cognitive biases in decision making, generally, dates to the pioneering work of Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman, but only more recently have researchers begun to consider how those biases play out in tax policy. Simplistically, income tax rates are relatively easy for taxpayers to see, and they will notice if Congress raises rates. But other provisions that have a similar effect of raising revenues—for example, the phaseouts on personal exemptions and deductions for the wealthy—may be harder to see, or less salient. Likewise, the failure to index tax brackets for inflation has the effect of changing a taxpayer’s marginal tax rate without altering the tax brackets.

Schenk argues that while such provisions often get criticized as hidden taxes, that criticism is misdirected; low-salience taxes might be both effective and justified. “Tax scholars are starting to think about how to adopt behavioral economics in tax,” Schenk says. “Can we use behavioral economics to shape compliance? Some people think that’s devious. There are a few of us who say we ought to take this into account.”

A dozen years after Schenk came to NYU Law, Daniel Shaviro, Wayne Perry Professor of Taxation, joined from the University of Chicago Law School. Shaviro, whose background includes stints at the elite tax firm Caplin & Drysdale and at the Joint Committee on Taxation (where he worked on the 1986 tax reform), has wide-ranging interests spanning tax policy, budgets, international tax, corporate tax, and more. He has written eight books on topics that range from budget policy to corporate tax—including Decoding the U.S. Corporate Tax; Taxes, Spending, and the U.S. Government’s March Toward Bankruptcy; Making Sense of Social Security Reform; and Do Deficits Matter?—and he pens an influential tax blog called Start Making Sense, in which he was outspoken in his criticism of Mitt Romney’s tax proposals during the recent elections. His rich body of work even includes a satirical 2010 novel with a young, morally challenged litigator as a protagonist.

A dozen years after Schenk came to NYU Law, Daniel Shaviro, Wayne Perry Professor of Taxation, joined from the University of Chicago Law School. Shaviro, whose background includes stints at the elite tax firm Caplin & Drysdale and at the Joint Committee on Taxation (where he worked on the 1986 tax reform), has wide-ranging interests spanning tax policy, budgets, international tax, corporate tax, and more. He has written eight books on topics that range from budget policy to corporate tax—including Decoding the U.S. Corporate Tax; Taxes, Spending, and the U.S. Government’s March Toward Bankruptcy; Making Sense of Social Security Reform; and Do Deficits Matter?—and he pens an influential tax blog called Start Making Sense, in which he was outspoken in his criticism of Mitt Romney’s tax proposals during the recent elections. His rich body of work even includes a satirical 2010 novel with a young, morally challenged litigator as a protagonist.

Shaviro’s big project at the moment is a forthcoming book on international tax policy, Fixing U.S. International Taxation, that will try to frame the issues regarding taxation of multinational companies in a global economy at a time when Washington has been considering corporate tax reform. Among the issues the book will explore is how to think about a territorial system of taxation, in which offshore profits would not be taxed in the US (which, corporations argue, would make them more competitive in a global economy), versus the current system in which overseas profits of US-based entities are taxed when they come back home, but those companies receive a credit for foreign taxes paid. Ultimately, Shaviro argues, the US lacks the market power to levy as much tax on US companies’ foreign-source income as it does on domestic income, and should use a lower tax rate for overseas income, instead of relying on foreign tax credits and deferral. (The current tax system, he notes, is what induced Apple to borrow in the US rather than bringing home more than $100 billion in offshore profits.)

While Shaviro has been working on the book, he has published numerous other papers, many of which have grown out of the research for the book. In “The Rising Tax-Electivity of US Corporate Residence” (Tax Law Review, 2011), which was first presented as the David R. Tillinghast Lecture at NYU Law, Shaviro looks at the ability of US corporations to elect a different residence for tax purposes and what that might mean to the current US system of international taxation. “In an increasingly integrated global economy, with rising cross-border stock listing and share ownership, it is plausible that US corporate residence for income tax purposes, with its reliance on one’s place of incorporation, will become increasingly elective for taxpayers at low cost. This trend is potentially fatal over time to worldwide residence-based corporate taxation, which will be wholly ineffective if its intended targets can simply opt out,” Shaviro writes. If the US were to shift its system of taxation, he argues, the US could assess a one-time transition on existing US multinationals’ foreign subsidiaries’ profits, which might raise $200 billion, to avoid giving a windfall to them.

Shaviro’s arrival at NYU heralded an increased depth of focus on tax policy, a shift from the earlier days of looking at tax doctrine. “That really took off with Dan,” says Noël Cunningham, whose own focus is on partnership taxation. “I think it’s fair to say that now, as a group, we’re more policy than doctrine.” For example, the work of Joshua Blank, who joined in 2010 as professor of tax practice, and Mitchell Kane, Gerald L. Wallace Professor of Taxation, who arrived in 2008, touches on repercussions for tax scofflaws, environmental policy, and economic development.

Shaviro’s arrival at NYU heralded an increased depth of focus on tax policy, a shift from the earlier days of looking at tax doctrine. “That really took off with Dan,” says Noël Cunningham, whose own focus is on partnership taxation. “I think it’s fair to say that now, as a group, we’re more policy than doctrine.” For example, the work of Joshua Blank, who joined in 2010 as professor of tax practice, and Mitchell Kane, Gerald L. Wallace Professor of Taxation, who arrived in 2008, touches on repercussions for tax scofflaws, environmental policy, and economic development.

“Collateral Compliance,” Blank’s recent University of Pennsylvania Law Review article, looks at collateral sanctions for tax noncompliance. Such sanctions are imposed in addition to monetary tax penalties, revoke non-monetary government benefits and services, and are often administered by agencies other than the taxing authority. In Kawashima v. Holder, for instance, the Supreme Court in 2012 upheld an immigration judge’s decision to deport a Japanese immigrant couple who had previously pleaded guilty to filing false tax returns and been sentenced to four months in prison. States also are trying to use collateral sanctions. In California, for example, tax delinquents may lose their driver’s license; in Louisiana, it’s their hunting license that’s at risk.

Blank argues that collateral sanctions should only be applied when there’s a violation of a clear tax rule, when the taxing authority identifies the offense, and when taxpayers view the sanction as proportionate to the offense—standards that aren’t met when incorporating the Kawashima holding into federal deportation policies. “I argue collateral sanctions offer a lot of benefits,” says Blank. “But if people view the penalty as disproportionate, they may not cooperate.”

In addition to projects involving individual tax compliance, Blank is also pursuing a long-term empirical study of the factors that influence judges’ decisions in corporate tax abuse cases with Nancy Staudt, a tax policy scholar at the University of Southern California Gould School of Law. “Corporate Shams” in the NYU Law Review (2012) reviewed more than 100 years of US Supreme Court decisions. The two are now immersed in thousands of federal appellate court decisions as they focus on the role of tax penalties in judicial decision making.

Meanwhile, Mitchell Kane is an international law expert who engages in cross-disciplinary research. His “Strategy and Cooperation in National Responses to International Tax Arbitrage” (Emory Law Journal, 2004) looked at the opportunities created by arbitrage—the structuring of transactions to take advantage of variations in tax laws across jurisdictions—for governments as they battle to attract capital in a global economy.

Kane is currently energized about work that spans tax and climate policy. At a conference in Europe, he realized that efforts to create carbon markets—which should have a single price to reduce emissions—have been hampered by the lack of a harmonized system for a carbon tax across jurisdictions. “All of the economic models are built on a pre-tax basis,” Kane says. “So I’ve been struggling with the general problem of how the tax system should be structured.” Kane’s “Taxation and Multi-period Global Cap and Trade,” published in the NYU Environmental Law Journal in 2011, tried to create a framework for the taxation of a greenhouse gas emissions permit market that encompasses multiple periods and jurisdictions.

Puzzles within puzzles

Despite the glitziness of talking tax policy, for most students the core reason to study tax law remains professional education in difficult and highly specialized tax issues. And it doesn’t take a lawyer to realize that as the tax code has gotten ever more complex, the amount of knowledge required to understand it has expanded exponentially. Over the last dozen years, National Taxpayer Advocate Nina Olson has consistently cited the complexity of the tax code as one of the biggest problems facing American taxpayers. Not only does the thicket of rules and regulations make compliance difficult, but it undermines trust in the tax system, too. The burden on the tax lawyer is that much greater as well. “You cannot begin to know it all. It’s wildly out of control,” Schenk says. Adds John Steines: “If you’re going to remain technically proficient, it’s much more demanding now. And as each decade rolls by, it becomes that much more demanding.”

Mastery of the tax code inspires such passion in members of the NYU Law tax faculty that, for many years after Marta closed, they would regularly gather at Volare, a cozy Italian restaurant near Washington Square Park known for its burlesque paintings by the Broadway set designer Cleon Throckmorton, and debate its arcane details. While friendly, those tax discussions occurred so often, and got so heated, that the restaurant allowed them to keep a copy of the entire Internal Revenue Code behind the bar to settle disputes quickly and definitely.

More seriously, the tax professors have used that refined and battle-tested knowledge to produce numerous treatises and casebooks that are at the core of teaching the practice of tax law. The B&E treatise on corporate taxation is the gold standard in that area and the most prominent example.

[SIDEBAR: The Most Influential Person in the Tax World]

Schenk wrote Federal Income Taxation: Principles and Policies (co-authored with Michael Graetz). Cunningham and his wife, Laura LLM ’88, a tax professor at Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law and adjunct at NYU, penned The Logic of Subchapter K: A Conceptual Guide to the Taxation of Partnerships, the definitive book on partnership tax law, a particularly abstruse subject. Brookes Billman, who has been teaching at NYU since 1979, co-wrote a casebook on tax procedure, Federal Tax Practice and Procedure: Cases, Materials, and Problems. Malman co-authored The Individual Tax Base: Cases, Problems, and Policies in Federal Taxation.

Blank credits Schenk and Graetz’s book on federal income taxation, which he first read in his dorm room during his JD studies at Harvard, with getting him excited about taxation, a subject many young law students don’t think they’ll enjoy. “After reading the first few pages, I was hooked,” he says.

The tax code, for students who are interested in it, is a brainteaser, creating puzzles within puzzles to work through. At NYU Law, as the tax code itself has grown more intricate, the number of tax courses has proliferated; there are now roughly 100 classes, more than any one student could possibly take. While the Graduate Tax Program caters to LLM students, JD candidates can take graduate-level courses, and those who want to focus their studies can pursue a joint JD/LLM degree. Classes range from the straightforward (Income Taxation, Taxation of Property Transactions, Estate and Gift Taxation) to the complex (Advanced Corporate Tax Problems, Taxation of Subchapter S Corporations) to the esoteric (Taxation of Affiliated Corporations). And while the 14 fulltime faculty (plus two acting assistant professors each year) teach many of the courses, adjuncts, who are often practicing attorneys at elite firms, handle some of the most complex topics—taxation of financial instruments, say, or taxation of private equity. “Unless you’re dead set on something else already, it’s such a good idea to try tax,” says Vivek Chandrasekhar ’11, LLM ’13, who clerked for Judge Rosemary Pooler of the US Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit in the 2012 term, and now works at Roberts & Holland, a boutique tax firm in New York.

Still honoring the collegial model that Wallace and Lyon created, the tax program offers students a dizzying array of colloquia, programs, and networking events outside of the classroom. Each year, Blank hosts roundtable lunches that feature prominent alums talking about how they became interested in tax and what led to their success in the field. “It’s our version of Inside the Actors Studio,” Blank says. Students also attend the annual David R. Tillinghast Lecture on International Taxation, the NYU/KPMG Tax Lecture Series, and even an annual tax movie night, which this year featured episodes from The Honeymooners and The Simpsons.

Still honoring the collegial model that Wallace and Lyon created, the tax program offers students a dizzying array of colloquia, programs, and networking events outside of the classroom. Each year, Blank hosts roundtable lunches that feature prominent alums talking about how they became interested in tax and what led to their success in the field. “It’s our version of Inside the Actors Studio,” Blank says. Students also attend the annual David R. Tillinghast Lecture on International Taxation, the NYU/KPMG Tax Lecture Series, and even an annual tax movie night, which this year featured episodes from The Honeymooners and The Simpsons.

As tax becomes more complex and the legal market changes, the Graduate Tax Progam has been adding even more classes that will better prepare students for jobs as tax lawyers. There are now more in-depth classes on issues in state and local taxation, for example, and specialized courses that focus on transactional tax planning. In a new course on tax deals, students read merger agreements and try to understand how the deal was structured and why. Another new offering focuses on accounting for tax consequences, a nod to the closer relationship between accountants and tax lawyers. “We are working with the faculty to incorporate a level of practical training into the substantive classes,” Blank says.

The faculty is also moving rapidly into online education, making sure that tax classes are available for time-pressed attorneys across the nation. Since 2008, NYU Law has offered the Executive LLM in Tax in an entirely digital format. “Our online program is thriving,” Blank says. It currently has roughly 100 students, several of whom are experienced partners in law firms and high-ranking lawyers in accounting firms. Blank and Graduate Tax Program Director John Stephens have worked closely with the faculty to expand the number of online courses offered. With streaming software that’s used by some of the most popular movie services, the online classes give the feel of being in the classroom, with chalkboard scrawls turned into detailed graphics. Adjunct Professor Sarah Lawsky, for example, created the online Tax Deals course. Tax ramifications are an increasingly important consideration in mergers and acquisitions, and the course seeks to give students real-life experience reading deal documents and exploring the tax provisions in them. The final exam is a deal document with questions.

Like many law students, Hayes Holderness ’11, LLM ’12 wasn’t initially interested in tax. But Schenk’s 1L income tax course changed that. After a tax policy fellowship at the Joint Committee on Taxation and an LLM in tax, he is now an associate at McDermott Will & Emery in New York focused on state and local tax issues. “The environment at NYU helped me to form not only a good understanding of the tax law,” he says, “but also a love for it.”

While students who will practice in the US hunker down in deals documents or learn the ins and outs of employee benefits law, an increasing number of foreign students choose to study tax in the US. A select few foreign students will study in the International Tax Program, launched in 1997. Director H. David Rosenbloom, James S. Eustice Visiting Professor of Taxation and member at Caplin & Drysdale in Washington, DC, describes it as a tightly knit intellectual oasis with a maximum of 30 students from around the world. “It’s very intensive,” says Rosenbloom, who is an expert in tax treaties, some of which he helped negotiate during his time as international tax counsel at the Treasury Department’s Office of International Tax Affairs in the late 1970s. “It’s an education in tax and in internationalism.”

While students who will practice in the US hunker down in deals documents or learn the ins and outs of employee benefits law, an increasing number of foreign students choose to study tax in the US. A select few foreign students will study in the International Tax Program, launched in 1997. Director H. David Rosenbloom, James S. Eustice Visiting Professor of Taxation and member at Caplin & Drysdale in Washington, DC, describes it as a tightly knit intellectual oasis with a maximum of 30 students from around the world. “It’s very intensive,” says Rosenbloom, who is an expert in tax treaties, some of which he helped negotiate during his time as international tax counsel at the Treasury Department’s Office of International Tax Affairs in the late 1970s. “It’s an education in tax and in internationalism.”

Tax policy might be more in vogue and intellectually interesting than tax practice, but the reality is that most tax lawyers will wind up at law firms. And as the legal market gets squeezed, having more specialized knowledge up front is not just an advantage but also a necessity. “It’s important for grads today to show prospective employers they can deliver immediate value,” Steines says. “Particularly in view of the economic condition of the legal profession, it is important that law schools not forget that most people view them as professional schools.”

Looking Forward

Benjamin Franklin famously said, “Nothing is certain except death and taxes.” Paying taxes, however much you may personally grumble about it, is part of the social contract. And as last year’s presidential debates heated up over the taxes paid by the one percent and what type of social safety net we as a country want to have, the critical role of tax policy was impossible to ignore.

While the fiscal cliff deal at the end of last year settled tax policy for individuals, both Democrats and Republicans have continued to talk about the possibilities for major tax reform, something that has not happened since 1986. Since last fall, both Senator Baucus (who has announced he will retire in 2015) and Congressman Dave Camp, chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee, have been working up their proposals and have issued 10 bipartisan options papers.

“We’re going full steam ahead,” Batchelder says. “The chairman really wants to do tax reform. It’s an extremely ambitious goal, and there are a lot of challenges, but we’re going to work as hard as we can to make it happen.”

The debates in Washington echoed back at NYU Law with a series of evening discussions called Pathways to Tax Reform, to look at ideas that range from the possible to the radical. What sort of tax reform should happen? What might it mean?

Interesting questions worth pondering, and studying.

—Amy Feldman is a New York-based business journalist. She writes a tax column for Reuters, and contributes to Fortune and Barron’s.

—