Legal Paper Makes Waves—Even Before Publication

Printer Friendly Version It’s not every day that a law review article challenges a piece of constitutional orthodoxy so widely held that junior high school students can recite it. And it’s even less common for law review articles to start generating discussion and controversy months before they are published.

It’s not every day that a law review article challenges a piece of constitutional orthodoxy so widely held that junior high school students can recite it. And it’s even less common for law review articles to start generating discussion and controversy months before they are published.

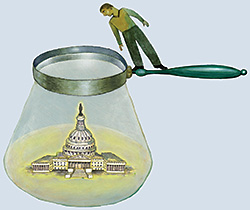

The June Harvard Law Review featured an exception to those rules, a collaboration between Sudler Family Professor of Constitutional Law Richard Pildes and Professor Daryl Levinson of Harvard Law School called “Separation of Parties, Not Powers.” It took aim at the conventional understanding of what is said to be the unique genius of the constitution: the checks and balances that are built into the separation of powers. Ambition checking ambition, in James Madison’s phrase, is said to be the very basis of the success of American democracy.

“The truth,” Levinson and Pildes wrote in the timely, fresh and immensely readable article, “is closer to the opposite.”

In an interview, Pildes explained that the article’s goal was to cause readers to reexamine the things they thought they knew. “The starting point,” he said, “is getting people to think more seriously about ideas, like ‘separation of powers,’ that are repeated so often they become taken-for-granted mythologies, without asking any more whether these institutions actually operate in the way these stories lead us to unreflectively believe.”

What the framers failed to envision, say Levinson and Pildes in their article, is how party politics can swamp the constitutional structure. When the same party controls both political branches, it is fantasy to think that Congress’s institutional self-interest will be enough to act as a meaningful check on the president. A single party has controlled government more often than not since 1832.

“Against this background,” the article says, “it is odd to hear courts and constitutional scholars celebrating government ‘accountability’ as a particular virtue, or even potential virtue, of the Madisonian design.”

Though the article was not formally published until June, it caught the attention of the legal academy in draft form. “It’s a very good and important paper,” said Cass Sunstein, a law professor at the University of Chicago. “It has a real insight that, certainly in the legal literature, is novel and fresh.”

He added that its thesis may in places be overstated, noting in particular that Senator Arlen Specter, the Republican chairman of the Judiciary Committee, has tried to protect Congressional power, though without notable success.

It is a mistake, the article says, to look to the courts for significant oversight of executive power when the political branches are controlled by a single party, as judges generally find presidential actions constitutional when they can be said to have been undertaken with Congressional authorization or, at least, silent acquiescence. Thus, the September 2001 Authorization for Use of Military Force was, the Supreme Court ruled in 2004, sufficient to justify military detentions. The administration relies on that same authorization in connection with its controversial surveillance program.

“Only during divided government,” the authors write, “do courts have the independence to act as a meaningful check on national majorities. In short, strongly independent judicial review may be possible only when least necessary.”

The article helps explain why Democrats are so eager to win back the House or Senate: Only an opposition party with subpoena power and similar oversight tools can truly act as a check on another branch. Indeed, among the reforms proposed in the article to compensate during periods of unified government is providing the minority party with such tools.

“Rather than blaming individual members of Congress for not playing their ‘assigned’ role of providing checks and balances and exhorting them to be more ‘responsible,’” Pildes said, “we need to look at the legal and institutional context in which they act and focus on changing that in ways that enable more meaningful checks and balances to be exercised in actual practice.”